by gulfnews.com — Bassam Za za, Special to Gulf News— Beirut: A video of a Lebanese protestor kissing Sky News Arabia’s anchor surprisingly while she was live on air went viral yesterday and triggered debate on social media. Lebanese popular anchor Darine El Helwe was on live broadcast with UAE-based Sky News Arabia from Riad Soloh Square […]

by news.mb.com.ph — Nearly four weeks into nationwide protests calling for the ouster of the ruling elite, radical changes demanded by demonstrators have not been implemented. The peaceful protests against corruption and sectarianism have paralysed Lebanon, worsening an economic crisis that has brought the country to the brink of default. Central bank governor Riad Salameh — increasingly under fire for his monetary policies — insisted however that deposits were safe and the country’s currency would remain pegged to the dollar. “The central bank’s first and foremost goal is to protect the Lebanese pound’s stability,” he told a news conference.

The bank has taken measures “to protect depositors and protect deposits”, he said. Salameh said he had asked local banks to lift restrictions imposed after protests started on October 17. Recent decreases in capital inflows have cause dollar shortages, leading banks to cap withdrawals. On the unofficial market, the greenback has sold at up to 20 percent more than its official rate. While Salameh insisted the financial sector would remain solvent, trust in the central bank has plummeted and outside the news conference dozens of protesters voiced their anger. “All of them means all of them. Salameh’s one of them,” they chanted, in a variation of a common call for all political figures to resign.

– Victory of sorts –

If a post shared on Instagram gets zero likes, did the moment even really happen? Instagram’s chief, Adam Mosseri, announced that beginning next week, Instagram will begin hiding the “likes” counter on some users’ accounts in the U.S. The users in the test will be able to see the likes on their photos or videos, […]

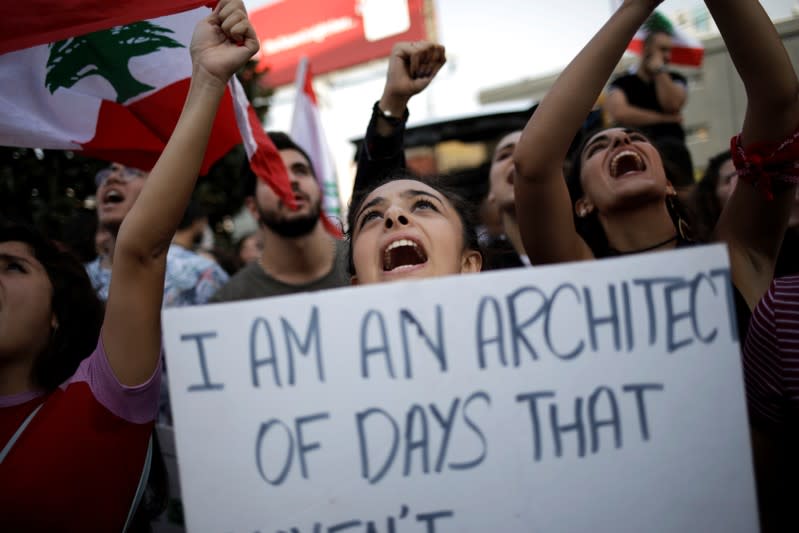

by gulfnews.com — Beirut: Beirut is a city awash with construction sites. Sleek condominium buildings are constantly being erected, towering over a population that increasingly cannot afford the cost of living. Developers have gobbled up the city’s public space and privatised beaches. But in recent weeks, protesters have begun reclaiming their city, tearing down the metal slats that boarded up the abandoned Grand Theatre, a pre-civil-war relic, and taking over the Egg, an oddly-shaped unfinished cinema, empty for more than 50 years. On the first two nights of unrest last month, the protesters hid in the abandoned structures from police wielding tear gas and batons. Wael Zorkot, 24, hunkered down with them until a column of security forces flushed them out and forced them down the street. He had been with the protesters from the beginning, airing his frustration over the political and economic conditions in his country.

Zorkot said he works at least four days a week bartending at two bars to pay for his education and living expenses, typically finishing at 4am and catching some sleep before going to class. His father owns three stores in their hometown of Zrarieh in southern Lebanon, selling clothes, toys and motorcycles, but life is still tough. His mother is battling cancer and flies to France every four months for treatment because it is too expensive in Lebanon. “I have a lot of plans,” he said about the future. “But not here.” Dozens of young protesters, when asked about their futures, also said they want to emigrate.

The Lebanese economy on average creates no more than 3,000 jobs a year, said Jad Chaaban, an economics professor at the American University of Beirut, but the need is at least 20,000. “There’s a huge mismatch, because of the bad situation in the country, the lack of economic reforms that stimulate job creation, the fact that the government is very corrupt and only invests in projects that are not geared for job creation,” Chaaban said. Lebanese college students benefit from a good education system but at graduation cannot find suitable jobs. He said they endure a period known as “waithood” – waiting for visas to emigrate and for things to change – and grow frustrated with the economic situation.

By Ellen Francis, Reuters — BEIRUT (Reuters) – Lebanese are protesting outside failing state agencies they see as part of a corrupt system in the hands of the ruling elite, as well as at banks they deem part of the problem. Protesters accuse sectarian political leaders of exploiting state resources for their own gain through networks of patronage and clientelism that mesh business and politics. Where have Lebanese protested and why?

ELECTRICITE DU LIBAN (EDL)

Lebanon’s electricity sector is at the heart of its financial crisis, bleeding some $2 billion in state funds every year while failing to provide 24-hour power. “This is one of the peak symbols of corruption,” said Diyaa Hawshar, an electrician protesting outside state power firm EDL in Beirut. “We pay two bills, one for the government and another for generators.” “It’s about carving up the cake, with deals on power barges and overhauling power plants, shady deals in public and under the table,” he said. “Every minister who comes makes promises. They come and go.” Power cuts can last several hours every day. People and businesses rely on so-called “generator mafias” who often have political ties and charge hefty fees to keep the lights on. The average household ends up paying $300 to $400 a month on average for electricity, said Jad Chaaban, economics professor at the American University of Beirut. Lebanon’s minimum wage is the equivalent of $450 a month. “It is an insult for a lot of people to keep paying for services that are dysfunctional and at the same time funding the parties and travel of corrupt leaders,” he said.

The government has for years touted plans to overhaul the sector including new power stations, fixing the grid and stopping electricity theft. But the Lebanese saw no tangible progress by the time the prime minister resigned last week. “People have to beg for their rights…for a few hours of electricity at home,” said Mia Kozah, a university student. “It should be one of the simplest matters. Enough humiliation.”

MOBILE OPERATORS

![Demonstrators block access to the state-owned electricity company during anti-government protests in Beirut, Lebanon [Andres Martinez Casares/Reuters]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2019/11/8/02087cf9ae4f4eedbfdfafa2eab6acce_18.jpg)

Reuters – Lebanese bank staff are facing abuse from customers angered by restrictions on their access to their cash, the employees’ union said on Friday, reflecting intensifying pressures in an economy gripped by its deepest crisis since the 1975-90 civil war. With Lebanon paralysed by political and economic turmoil, its politicians have yet to make progress towards agreeing on a new government to replace one that was toppled by an unprecedented wave of protests against the sectarian ruling elite. Saad Hariri, who quit as prime minister last week, is determined that the next government be devoid of political parties. A sectarian cabinet would not be able to secure Western assistance, a source familiar with his view told the Reuters News Agency. He is still seeking to convince the powerful, Iran-backed Shia group Hezbollah and its ally the Amal Movement of the need for such a technocratic government, the source said. Hariri’s office could not immediately be reached for comment.

Leading Christian politician Samir Geagea warned of great unrest if supplies of basic goods run short and said Lebanon’s financial situation was “very, very delicate”. One of the world’s most heavily indebted states, Lebanon was already in deep economic trouble before protests erupted on October 17, ignited by a government plan to tax WhatsApp calls and taking aim at rampant state corruption.

‘Clients with guns’

by catholicherald.co.uk — A long-awaited decision to restore a celebrated church in Iraq desecrated by ISIS has been hailed as a turning point in the struggle to keep Christianity alive in one of its most ancient heartlands. Syriac Catholic Archbishop Petros Mouche of Mosul thanked Aid to the Church in Need (ACN) for committing itself to repair the Great Al-Tahira Church (Church of the Immaculate Conception), Qaraqosh (Baghdeda), the largest Christian town in the Nineveh Plains. The plan to restore the church’s fire-damaged interior is one of a series of building projects across Nineveh announced by ACN. Speaking to ACN, Archbishop Mouche said: “For us, [the Great Al-Tahira] Church is a symbol. This church was built in 1932, and it was the villagers of Baghdeda who constructed it. “For this reason, we want this symbol to remain as a Christian symbol to encourage the people, especially the locals of Baghdeda, to stay here. “This is our country, and this is a witness that we can give for Christ.”

ACN has approved 13 other projects to rebuild church properties across the region – all of them damaged and desecrated by ISIS. The charity approved plans to reconstruct the Najem Al-Mashrik Hall and Theatre in Bashiqa, a town occupied by both Christians and Yazidis – a project which will enable the venue to once again play host to wedding ceremonies and other celebrations. Local priest Fr Daniel Behnam said: “This project will help ensure the survival of Christian families and provide them with important services. “In particular, it will help young people, providing a space for pastoral, cultural and youth activities.”

by reuters.com — By Tom Perry and Tom Arnold — BEIRUT – Lebanon’s outgoing Prime Minister Saad al-Hariri met President Michel Aoun on Thursday without announcing progress towards forming a new government, and banking sources said most financial transfers out of the country remained blocked. Already facing the worst economic crisis since the 1975-90 civil war, Lebanon has been pitched deeper into turmoil since Oct. 17 by a wave of protests against the ruling elite that led Hariri to resign as prime minister on Oct 29. Banks reopened on Friday after a two-week closure but customers have encountered restrictions on transfers abroad and withdrawals of hard currency.

A banking source said that generally all international transfers were still being blocked bar some exceptions such as foreign mortgage payments and tuition fees. A second banking source said restrictions had gotten tighter. Hariri has been holding closed-door meetings with other factions in the outgoing coalition cabinet over how the next government should be formed, but there have been no signs of movement towards an agreement. Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri said he wanted Hariri to be nominated as prime minister again. Under Lebanon’s sectarian power-sharing system, the prime minister is a Sunni Muslim, the president a Maronite Christian and the speaker a Shi’ite.

Aoun has yet to formally start consultations with lawmakers over nominating the new prime minister. The presidency said Aoun and Hariri discussed contacts aimed at solving “the current government situation”. The protesters have called for a new government that would exclude leaders of Lebanon’s traditional sectarian political blocs. But politicians are still wrangling over its shape. Hariri has held two meetings this week with Gebran Bassil, a son-in-law of Aoun. Both Aoun and Berri are allies of the powerful Iran-backed Shi’ite group Hezbollah.

“A HUGE” COLLAPSE AHEAD

BY foreignpolicy — BILAL Y. SAAB –– The author of this controversial decision is U.S. President Donald Trump’s National Security Council (NSC), which broke with the enduring U.S. bipartisan consensus on Lebanon policy. But as bold as the White House’s action is, it should come as no surprise. NSC staffers with responsibility for the Middle East have been aggressively trying to repurpose and downsize Lebanon’s military assistance program for more than a year. The effort was spearheaded by former National Security Advisor John Bolton, but it continued apace even after his ousting by Trump on Sept. 10. Even though the Office of Management and Budget did not give a reason for the funding suspension, the NSC’s case should be familiar by now: It argues that Hezbollah controls the Lebanese government and poses a security threat to Israel, and until the LAF shows a greater commitment to challenging the militant party, U.S. military aid will decrease. There’s another argument for the aid freeze that may have little to do with Lebanon. Since assuming office, Trump has strongly favored cutting foreign aid in general because he believes that the United States is not getting enough back from its friends. The NSC has fulfilled his wish by instituting a new foreign assistance policy that is more frugal and more aligned with his “America First” vision. As a recipient of U.S. aid, Lebanon, like several other countries, was a target of cuts—and now a freeze.

None of the NSC’s concerns about Lebanon and Hezbollah are inaccurate or unreasonable. These concerns are shared by senior leadership in the Defense and State departments and U.S. Central Command. Hezbollah, which has more guns and combat experience than the Lebanese military, does wield tremendous influence over politics in Beirut. It alone decides when the country goes to war or makes peace, and it has a predominant say in who gets to be president and prime minister. But the disagreement in the U.S. government is not over the challenge Hezbollah represents to both Lebanon and U.S. policy. That is all crystal clear. Rather, it is over how to most effectively address this challenge. The White House views Lebanon through the narrow prism of its maximum pressure campaign against Iran. And it seems to believe that halting aid to the Lebanese military will somehow compel its leadership to confront Iran’s main ally, Hezbollah. Not only is this based on faulty logic, but it is incredibly ill-advised. The Lebanese military does not have the means, inclination, or authority to forcefully counter Hezbollah. All it can do is continue to present itself to Lebanese society as a credible alternative to the Shiite group, which is a long-term process. Its leadership understands that any attempt at confronting Hezbollah, which even the mighty Israeli army couldn’t do successfully, will result in the splintering of the military along sectarian lines and the possible return to civil war.

by foreignpolicy.com — Michal Kranz — Expectations were high for Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah’s speech on Nov. 1, which arrived at the end of a tumultuous week in Lebanon that included widespread street violence in Beirut and Prime Minister Saad Hariri’s resignation after two weeks of nationwide protests. But the militant group’s leader had little to say. Like in his previous speech on Oct. 25, Nasrallah stressed pragmatism over idealism and delivered bland criticisms of Lebanon’s politicians while echoing their calls for a speedy government formation process following Hariri’s departure. “We call for dialogue between political parties, parliamentarians, and honest leaders of the protests,” Nasrallah said. “We must all get past the wounds that were created in the last two weeks.”

For the leader of a party that has branded itself as the vanguard of Lebanon’s grassroots resistance for decades, Nasrallah’s backing of the country’s corrupt establishment might seem odd. Yet for now—struggling to adapt to the sudden changes in the political system around it and on the ground beneath it—the group has left itself with few alternatives other than backing the current order and betting on the power of its brand and its ability to dispense violence and threats to keep its supporters in line. Hezbollah will almost certainly be able to weather the growing storm and will retain its powerful position in Lebanese politics—but Hariri’s resignation, together with the social and political uncertainty that has resulted from the protests, has left the group looking unmoored. Through careful deal-making, success at the ballot box, and calculated use of force over the last decade and a half, Hezbollah has played a key role in crafting a political reality in Lebanon that has allowed the group to maintain stability, expand its missile arsenal, and to use the country as a reliable base from which to wage a campaign in Syria on President Bashar al-Assad and Iran’s behalf.