by english.aawsat.com — Lebanon’s Cardinal Patriarch Mar Bechara Rai called on Wednesday for the government to agree a plan with the International Monetary Fund to save the country from financial collapse and said elections should be held on time later this year. The Lebanese government began a new round of talks with the IMF last […]

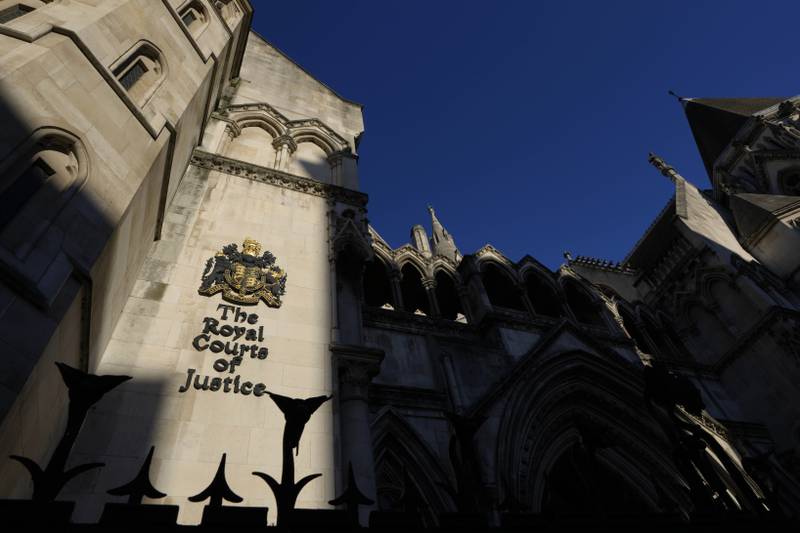

By Paul Peachey — thenationalnews.com — A British-Lebanese businessman is suing two banks who refused to transfer $4.6 million out of Lebanon following the 2019 economic crisis. Vatche Manoukian, 42, repeatedly asked SGBL (Societe Generale de Banque au Liban) and Bank Audi to transfer money to a Swiss account from 2019 but the two lenders refused, citing informal capital controls imposed by the country’s central bank. Mr Manoukian is demanding the return of the $3.4m held in SGBL and the $1.2m held in Bank Audi, plus damages and interest. The banks are contesting the claims. The case comes after a French court ordered another Lebanese bank, Saradar, to pay $2.8m to one of its clients in France last year in the first known international ruling against Lebanese banks over the capital controls.

Mr Manoukian’s claim is a rare case being heard in London, which has been brought under EU consumer legislation that was in place before Brexit. The case has been fast-tracked at the High Court because of the deteriorating financial situation in Lebanon. Lebanon’s financial system collapsed in 2019 after years of unsustainable financial policies, and banks imposed tight controls on accounts, including a de facto ban on withdrawals of dollar-denominated deposits and limits on withdrawals in the local currency. These controls were never formalised with legislation and have been challenged in local and international courts by savers who have sought to take out their money promptly in hard currency, rather than in the Lebanese pound, which has lost more than 90 per cent of its value in two years.

By Mark Jenkins — catholicherald.co.uk — In 2014 Vladimir Putin recommended three books for his regional governors to read: Justification of the Good, by Vladimir Solovyov; Philosophy of Inequality, by Nicholas Berdyaev; and Ivan Ilyin’s Our Tasks. Although each of these writers had very different visions, they were all united by a belief in “The Russian Idea:” the belief that Russia has a unique, providential, indeed messianic role to play in world affairs. The political philosophy of Ivan Ilyin (1883-1954) is known to have struck a particular chord with Vladimir Putin – to the extent that in 2005 the Russian President ordered that Ilyin’s remains be moved to the Donskoy Monastery in Moscow. During his life, Ilyin had been a fervent Russian Orthodox churchman. Ilyin saw Russia as an organic being, an extra historical, mystical unity, rather than in terms of the kind of legalistic understanding of nationhood that had emerged out of the European Enlightenment. Like Dostoevsky, Ilyin believed in the importance of Russia preserving its tradition of autocracy, as well as avoiding the nineteenth-century western fashion for constitutional government.

In 2014 Vladimir Putin recommended three books for his regional governors to read: Justification of the Good, by Vladimir Solovyov; Philosophy of Inequality, by Nicholas Berdyaev; and Ivan Ilyin’s Our Tasks. Although each of these writers had very different visions, they were all united by a belief in “The Russian Idea:” the belief that Russia has a unique, providential, indeed messianic role to play in world affairs. The political philosophy of Ivan Ilyin (1883-1954) is known to have struck a particular chord with Vladimir Putin – to the extent that in 2005 the Russian President ordered that Ilyin’s remains be moved to the Donskoy Monastery in Moscow. During his life, Ilyin had been a fervent Russian Orthodox churchman. Ilyin saw Russia as an organic being, an extra historical, mystical unity, rather than in terms of the kind of legalistic understanding of nationhood that had emerged out of the European Enlightenment. Like Dostoevsky, Ilyin believed in the importance of Russia preserving its tradition of autocracy, as well as avoiding the nineteenth-century western fashion for constitutional government.

by arabnews.com — HEBSHI ALSHAMMARI — RIYADH: A Lebanese woman flown on an emergency flight from Beirut to Riyadh is receiving urgent lung and breast cancer treatment following a generous intervention by Saudi Arabia’s King Salman. Sahar Ali Karim was aided by the Saudi Ministry of Health in her transfer to the world-class King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center on Monday. The facility is the largest cancer treatment center in the Gulf region. It is accredited by the World Health Organization as a Collaborating Center for Cancer Prevention and Control. Saudi authorities had begun the process of transferring Karim after Saudi Arabia’s King Salman issued a directive to treat her cancer, which had led to bone metastasis. Karim’s husband thanked King Salman and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman on Twitter for sponsoring the treatment of his wife. He said: “A distress call from Lebanon, and a generous hand answered it from Riyadh, the capital of the Kingdom of humanity. Thank you, Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques King Salman for your generous agreement to treat my wife’s cancer. I’m asking God Almighty to make her in the balance of your good deeds.” He added in the viral tweet: “Praise be to God … how much hope and life this approval has made in us.”

Ahmed Al-Fuhaid, an academic and member of the board of directors of the Saudi Journalists Association, said: “It is important for governments to deal with humanitarian conditions in isolation from the interactions and disagreements that occur between countries.” He added that Saudis, since ancient times, have sought to do good and provide aid to those in need, and that “people here take the initiative to extend a helping hand to meet the needs of people inside and outside the country.” Al-Fuhaid said that such aid takes many forms, including financial and in-kind donations including food, medicine and clothing, in addition to support of tools, products and services. He added that Saudi aid to needy people around the world “is clearly evident through the figures issued by international organizations,” and that the Kingdom’s generosity on a state level is “a reflection of the personality and nature of the Saudi people.”

NNA – President of the Republic, General Michel Aoun, met Prime Minister, Najib Mikati, today at Baabda Palace, and discussed with him general conditions and the atmosphere of the Cabinet’s discussions of the draft budget law for the year 2022, in addition to the electricity file and the necessity of taking steps that determine its course definitively and clearly. Statement: After the meeting, PM Mikati made the following statement: “I met His Excellency the President and briefed him on the atmosphere that prevailed in recent days, in terms of discussing the draft budget within the Council of Ministers and finalizing it in the next session, God willing, in preparation for submitting it to the Parliament in its final form. We agreed to hold a Cabinet session next Thursday in Baabda Palace at 2:00 pm, provided that the Cabinet will finish studying the budget on the same day, even if the session took hours.

I conveyed to President Aoun, greetings from the Turkish President and his keenness on the best relations with Lebanon, and in view of the accumulated issues that must be studied in the Council of Ministers, I informed the President of my invitation to the Council to convene next Tuesday in the Grand Serail to take the appropriate decisions.

By NAJIA HOUSSARI — arabnews.com — BEIRUT: Politicians, ambassadors, academics and representatives of international organizations took part in a “consultative meeting to save the education sector in Lebanon” on Monday, held by the Ministry of Education, against the backdrop of an ongoing teacher strike. The strike has contributed to paralyzing public schools for over four months, majorly disrupting the academic year “We do not have a magic wand to address all educational issues at once,” Prime Minister Najib Mikati said as he opened the meeting. “We hope the educational staff would understand the government’s situation and the limited capabilities we have. “We hope they can be patient, along with the students’ families, in light of the stifling economic crisis that coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic. “We ask teachers to cooperate with us to overcome this difficult stage with minimal damage and not to throw demands at the government, students and families, as the state of the public treasury cannot handle any spending outside the most urgent issues.”

Education Minister Abbas Al-Halabi said that public school students “have barely attended 25 days of school this year, while students in the private sector are close to completing the curriculum.” This, he said would lead to huge disparity in academic outcomes unless “we are able to compensate for the lost months in public schools and complete the curricula before we reach the point of no return.” There are no accurate figures about the number of students in public schools for the year 2021-2022, but there were around 342,303 students in 2019-2020, with an increase in 2020-2021 of about 10,000 students, who switched from private schools due to an inability to pay fees amid the country’s soaring currency and economic crises.

NNA – Maronite Patriarch, Cardinal Bechara Boutros al-Rahi, presided over Sunday Mass in Bkirki this morning, whereby he emphasized in his homily: “It is not acceptable to allow practices that undermine constitutional institutions, and it is unacceptable to overthrow the independence, prestige and dignity of the judiciary, and that some judges lose their independence.” He […]

By Bassam Zaazaa – arabnews.com — BEIRUT: A Lebanese man was released on bail this week after a fortnight in detention for taking people hostage and threatening to blow a bank up while trying to withdraw $50,000 of his own money. Abdullah Al-Saii armed himself with a gun, grenade and bottles of benzene before entering […]

by arabnews.com — Najia Houssari — BEIRUT: In anticipation of US Envoy for Energy Affairs Amos Hochstein’s expected visit to Lebanon next week to discuss maritime border demarcation, Lebanon sent a letter to the UN “to shift negotiations on the southern maritime border from Line 23 to Line 29, while retaining the right to amend Decree No. 6433 in the event of reluctance and failure to reach a fair solution.” The letter explicitly states that “the area between lines 1 and 23 to the area between lines 23 and 29, with an increase of 1,430 square km in addition to the previous 860 square km, is the disputed area, including the Karish gas field.” In this letter, Lebanon does not abide by the “oil field in exchange for an oil field” negotiation principle, i.e. the Qana field in favor of Lebanon versus the Karish field for Israel. Rather, it includes a clear indication that the Karish field “is a disputed area, and Israel cannot continue its exploration operations nor begin extraction operations.”

Lebanon’s letter stresses that “the Israeli action in that disputed area endangers international peace and security.” This development is considered an escalation by Lebanon to speed up indirect negotiations with Israel, which are being handled by the US under UN auspices. The letter, addressed under the guidance of President Michel Aoun to the president of the Security Council on Jan. 28 and whose contents were just made public, stipulates that Lebanon adheres to its right to an area of 2,290 square km and not 860 square km only. A political observer told Arab News that Aoun had sent the letter to the government but did not receive a response approving or objecting to it. “The letter included a veiled threat aimed at accelerating negotiations and making achievements before Aoun’s mandate ends, and perhaps opening closed political doors for his son-in-law, MP Gebran Bassil, to recommend him as his successor,” the observer said. The letter read: “Out of respect for the principle of the ‘negotiating path’ that was not reached after the indirect negotiations, one cannot claim that there is a proven Israeli exclusive economic zone, contrary to what the Israeli side claimed regarding the so-called Karish field.”

*بيان صحفي لمجلس الأمن حول لبنان* https://alhadeel.net/article/323037/ البيان يطالب لبنان التقيد باعلان بعبدا للاطلاع ان البيان الصحفي في مجلس الامن يتطلب موافقة ١٥ عضو على ١٥ او ١٤ موافق وواحد نأي بالنفس عن التصويت او ١٣ موافق و٢ نأي بالنفس. اذا احد الاعضاء رفض نص البيان فلا يمكن اصداره