Beirut, Lebanon (CNN) Tamara Qiblawi — Iran-backed Hezbollah lost its parliamentary edge in a high-stakes election last weekend. For Lebanon, this could mean everything, or nothing at all. The country’s new parliament remains largely split between pro-Iran and pro-Saudi blocs. Hezbollah still commands the largest single parliamentary bloc and the new political makeup signals that the country is headed, yet again, for a costly stalemate. Yet within those apparently immutable divisions, important political shifts have taken place. Reformists from outside Lebanon’s traditional political establishment won around 10% of the seats. The reformists dislodged, if marginally, the dominance of an old political elite. This worked against Lebanon’s most powerful political party. When Hezbollah’s bloc lost a majority that underpinned the last four years of Lebanese politics, it was an unusual setback.

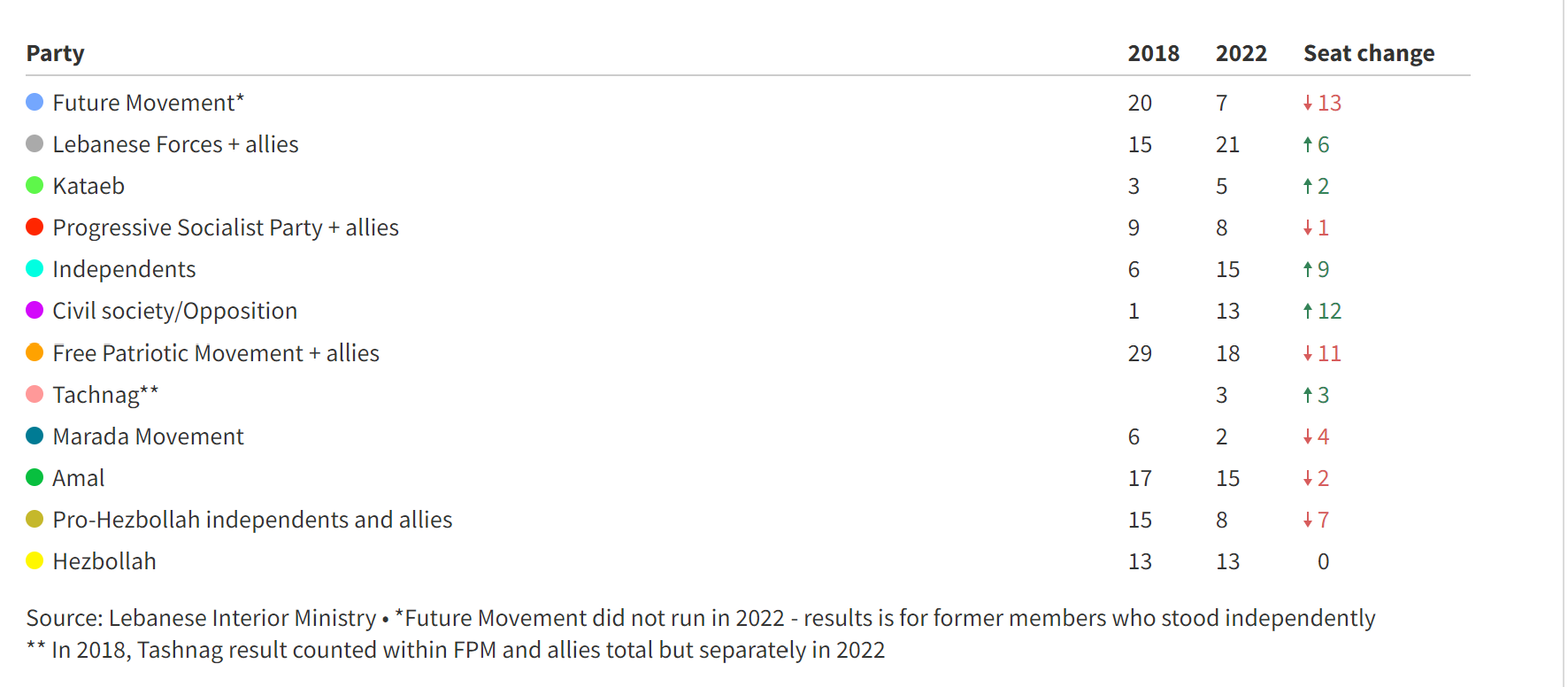

The group had gotten used to victory over the years. In 2000, it drove Israeli forces out of southern Lebanon after 22 years of occupation. In 2006, it held its ground in a war against Israel when Israel sought to disarm the group. During Syria’s civil war, it successfully intervened on behalf of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and helped bolster his defenses after the dictator violently quashed a popular uprising against his rule. The group’s political influence appeared to be on a relentless rise, despite a domestic bid — backed by Saudi Arabia — to curb the group’s power that was rapidly extending beyond Lebanon. But the weekend’s election marked a reversal of fortunes. While the parliamentary makeup of Hezbollah and its Shia ally, Amal, remains intact, a number of the group’s allies were unseated or beaten, mostly by reformists.

Analysts said this pointed to a loss in the group’s once formidable mobilization power. This could be a sign of growing frustration among Hezbollah’s constituents with the way it has handled a devastating economic crisis — and its increasingly heavy-handed intimidation tactics against dissent, including its attempts to stifle an investigation into Beirut’s 2020 port blast. It is unclear how Hezbollah will respond to these losses, or how the country’s new parliament will chart its course forward amid a financial tailspin. Those in parliament who oppose Hezbollah are an inchoate cluster of parties and independent candidates, with the Saudi-allied right-wing Christian Lebanese Forces (LF) representing the largest parliamentary bloc among them. The LF is a civil war-era militia-turned-political party, a far cry from the change that the masses called for when nationwide demonstrations engulfed the country in October 2019.