By James Owen, Published: March 31 2006 15:03, However hard you squint into the sun as it sets red over the Corniche, Beirut nowadays does not much resemble the

By James Owen, Published: March 31 2006 15:03, However hard you squint into the sun as it sets red over the Corniche, Beirut nowadays does not much resemble the

Yet something has endured and it is well worth seeking out. Nothing evokes the true spirit of a country more than its food and that of Lebanon is among the world’s most uplifting. Generations of students might disagree but there is far more to Middle Eastern cuisine than kebabs and connoisseurs acknowledge that of the Levant to be the region’s finest.

This place has always been a crossroads between the sea and the mountains, subject to the influence of wandering Phoenicians, warlike Arabs, invading Franks and, above all, imperious Ottomans, that dynasty whose tastes still feed the eastern Mediterranean: moussaka, that most characteristically Greek of dishes, is in fact an Arabic word that means “warmed up”.

One of the curiosities of Lebanese cooking is that the star of the meal is not the main course but the starters, the elaborate banquet of mezzes by which every Levantine mother-in-law still judges the skills of her son’s bride. Again, there are far more of these than the staples known to western supermarkets, the hummuses and baba ganoushes. Sumac and orange blossom, mallow leaves and cinnamon are flavours once familiar in Europe, but now they provide an entrée to a more exotic culture.

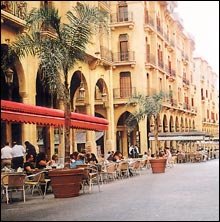

I tried a few at a table on the pavement outside Karam, a smart but unflashy restaurant on the edge of the CBD. Soon the table was spread with a spring meadow of colour, presentation being considered a vital part of a dish’s allure. To the cool green of mint was alloyed the scarlet of paprika, all framed by the polished ivory of bowls of yoghurt and stacks of warm bread. Tahini, aubergines and olives jostled for space, elbowed aside by chicken livers and a dish of tangy Lebanese Roquefort mixed with tomatoes.

The emperor of this menu is tabbouleh, a salad whose key ingredients are diced parsley and dried cracked wheat, although their mere description hardly prepares one for the explosion of freshness that fizzes across your tongue. An important rule, my waiter told me, is not to sully the flavours by eating it with a fork or a scoop of bread, but to use instead a crisp lettuce leaf as a kind of ladle. He might have added that you should also pace yourself and remember that this is just the first course.

The 10-minute drive over to Achrafiye, historically the city’s most refined quarter, acts as a rapid tour of Beirut’s past and present. To the urban symphony of squawking car-horns that is the background music of the Middle East, you race past shiny new hotels, spot-lit old churches, reminders of the civil war and the tombs of former premier Rafiq Hariri and others killed with him, murdered by a car bomb in February last year. Everyone is in a hurry.

The top-floor bar of the Albergo hotel offers a change of pace, where one can lounge comfortably on a sofa and look over the city while enjoying a drink. The fashionable décor seems to have strayed in from the backlot of a Marlene Dietrich film but its sense of theatre puts one in the mood for a couple of dishes just up the street at one of Beirut’s most atmospheric restaurants.

Al Mijana is set in a splendidly restored townhouse and its walled garden and its set menu offers one of the country’s specialities, kibbeh, a pulverised combination of lamb and onion rolled into moist torpedo-shaped rissoles. It is also where I was introduced to Lebanon’s lethal national drink, arak – lion’s milk.

Like its kin ouzo and raki, this is an aniseed-based brandy and at 30° proof it can cloud the head as rapidly as it does water once the two are mingled. The Lebanese, who sip it continuously through meals, say it is vital to give the two elements time to mix properly. I suspect that the secret to surviving it is to keep cutting it with ice, as they do. A post-dinner cup of dark, cardamom-spiced coffee, also works wonders.

The Lebanese table offers almost every variety of fruit in season, from pomegranates to figs to jujubes, while labneh, or yoghurt, is both a dish and a language lesson in one: its name derives from the Semitic word for “white”, and the country’s snow-capped mountains are the reason it bears the name it does. I, however, fancied a stickier treat and walked up through the CBD’s pedestrianised streets to perhaps its best-known patisserie Rafaat Hallab.

Purists will tell you that Tripoli, further along the coast, is the real home of Lebanese sweets, but this is a branch of one of that city’s most respected confectioners and the staff proudly talked me through their range.

Its elaborate forms and subtle combinations extend far beyond mere baklava, incorporating almonds, pistachios, pine nuts, syrup and even sweet cheese to make slabs of Taj el Malikor (“Throne of the King”) and my favourite, nammoura, fashioned from rose water and ground coconut. Beirut may yet become just another rich man’s playground but as I wandered off into the night, teeth sunk deep into sugar, I knew that some of the good things in life would always be within reach of even my budget.