ROUMIYEH, Lebanon (Reuters)

ROUMIYEH, Lebanon (Reuters)

Anwar, who has not seen his family in Baghdad for 11 years, said the theater project, in which he plays the jury foreman, had channeled his anger and saved him from fatal despair.

"I was going to commit suicide in the new year, but I have changed my mind," he said. "Before I felt like a criminal, like garbage, but now I feel respected, even by the prison officers.

MISSION IMPOSSIBLE

Daccache’s venture, sponsored by a local human rights group, funded by the European Union and managed by the Ministry of State for Administrative Reform, is unusual in the Arab world.

"I thought: Lebanon? No, it’s mission impossible," said the 30-year-old actress and drama therapist, who was inspired by visiting a similar project in an Italian prison in 2002.

It took her a year to get the money and another to win the go-ahead from wary authorities, but the prisoners are now set to stage their play for guests at the jail in February and March.

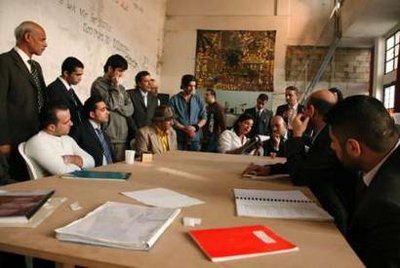

Prison authorities posted no guards inside the makeshift theater where Daccache rehearsed her 45 charges.

"She’s like a window of hope for us," said Hussein, a lank-haired graphic designer serving a five-year drug term who plays guitar in the play’s interludes of music and song. "Zeina will become a legend. She really did something for all of us."

The boisterous group, chosen from an initial 150 volunteers, is mostly Lebanese, but also includes Egyptians, Palestinians, Syrians and an Iraqi, plus two Nigerians and a Bangladeshi.

Daccache adapted the play "12 Angry Men" by U.S. author Reginald Rose, for local conditions and her own purposes. She has two sets of jurors to give more prisoners a chance to act.

The death penalty, at the heart of the drama made into a film in 1957 by director Sidney Lumet, is still on the books in Lebanon. Executions are rare, however. The last three were in 2004.

Several of Daccache’s actors are convicted murderers — one of the "jurors," a soft-spoken middle-aged Egyptian, has spent 14 years in Lebanon on death row.

In Roumiyeh, scene of a prison riot in April, the guards have noticed a change among the drama group.

"We have seen more motivation. Prisoners feel someone is paying attention to them," said the supervisor of the wing that contains the theater. "It has lowered the pressure 70 percent."

Daccache has enlisted a psychologist to do independent tests on members of her troupe and a control group of other prisoners. "We haven’t finished the study, but we already see a huge difference between where they were and where they are," she said.

The project takes up all her time. Two rehearsals a week have become five. So why sacrifice those extra hours, and then more to haggle with donors, bureaucrats and prison officials?

"I am happiest when I am inside the prison," Daccache says with a grin. "There you are dealing with really authentic people. If a guy is angry, he is really angry. Outside we fake so many things.

"Here they don’t, maybe because they already lost everything they are ready to restart from zero. We go easy on ourselves, but they don’t. They want to prove something, there is something they want to say, and this is the beautiful thing."

(Editing by Andrew Dobbie)