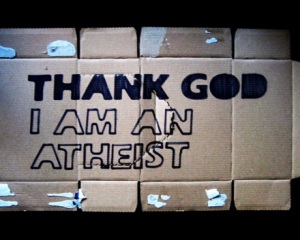

There is No Such Thing as a Thankful Atheist

Anyone who believes that he has gifted himself with his own being, that he is a self-caused being, that he is causa sui, is irrational. And if he really believes that and not just be contrarian or stubborn for the sake of it, he is certainly insane.

Until the scientist learns to give thanks, he will never get to the answer of contingent existence.

To confront the reality of our contingent existence means–if we are to use our highest form of thought–that we give thanks, that we be grateful. And this, ultimately, yields to faith, what G. K. Chesterton called "faith in receptiveness," a faith in receptiveness which gives rise to a receptiveness to faith.

When each of us confronts the raw fact "I exist," "I am," we also know that we need not have existed. We know, in fact, that there was a time that we did not exist, a time that we were not. And we can infer with absolute certainty from those who die about us and from our understanding of nature and time, that there will be a time where we will not exist, at least not in the way we do now.

"I am. I live. Some time before, I was not; I was not alive. There will be a time in the future where I will not be as I am now; I will die." These are unshakeable truths about our existence.

Those who deny them, we classify as insane. For example, we classify those people who say they are Napoleon insane because we know that Napoleon has come and gone. We treat similarly those people who insist that they are God and will never suffer death as insane.

Normal people know they are contingent beings who strut and fret their hour upon a stage and then are heard no more.

So it is a raw, incontestable fact that we are contingent beings.

Since we are contingent beings, we have not given being to ourselves. Our being is received. It is a gift. It is undeserved, not merited. Nothing we did can explain, can be the cause of, our having received existence. This is an undeniable reality it seems to me.

Anyone who believes that he has gifted himself with his own being, that he is a self-caused being, that he is causa sui, is irrational. And if he really believes that and not just be contrarian or stubborn for the sake of it, he is certainly insane.

Now, if we have any sort of wonder in us, we are bound to ask the question in light of the plain fact that we are contingent beings, "What (or Who) is the cause of my being?"

It takes a certain mindset to answer that question. It takes an open mind not wed to prejudice. As G. K. Chesterton famously wrote: "Merely having an open mind is nothing. The object of opening the mind, as of opening the mouth, is to shut it again on something solid."

Actually, having an open mind is something, in fact it is a very important thing if it is used to shut it again on an answer of our contingency.

Unfortunately, some of the most closed-minded of our fellows are scientists, particularly those who take the position that science and God are incompatible because God cannot be proved by science.

They operate under the limiting presumptions of what the historian of modern secularism Charles Taylor has called an "immanent frame," a frame of reference which excludes anything outside of the immanent (the material, the contingent) and excludes–for no reason at all, that is by human faith alone–the transcendent (the spiritual, the non-contingent).

Those with this kind of a scientific mindset put themselves in what Max Weber called an "iron cage," a mental prison which excludes anything of spirit, anything that cannot be verified by experimental science (empiricism).

These dreamless men labor under what the poet William Blake called the "single vision" of "Newton’s sleep."

They have exchanged what Fr. Thomas J. Norris describes as "hard reason," and have adopted in its stead "weak reason."

Whatever image you use–an iron cage, sleep, weakness, a frame–the real problem with the scientific mindset, at least in so far as it seeks to answer the question of contingent existence, is the lack of thanks.

Scientific reasoning, whatever its merits (and it has merits to be sure), is, at the same time, not the highest form of thought. It is not the highest form of thought because, if G. K. Chesterton the Apostle of Common Sense is to be believed, scientific thought does not give thanks.

How can you thank the Big Bang?

Who is to be praised for putting together the Primordial Soup?

To Whom do you pay sacrifice for Evolution?

How can you worship Natural Selection?

To be sure, the scientist may go back and explain our contingent existence by other contingent existences, and he may even try do so through a lengthy chain of, say 7 billion years or more. But such exercises smell of what Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI in his recent letter to the atheist mathematician Pierregiorgio Odifreddi called "fantascienza," science fiction, fantastical science or scientific fantasy.

The better of these theories, Benedict XVI agreed, approach or struggle to approach the transcendent, in which case one might call them "visions and ancticipations," struggles to reach knowledge. But they are, ultimately, unable to approach the whole of reality. There is a lot of this wishful thinking, he suggests, in a materialistic of evolution as even coming close to explaining contingent being.

But most of these efforts are just plain fantasy written using scientific concepts and scientific words. There are many mountebanks selling quack science. Benedict XVI points to Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene as a classic example of sheer fantascienza.

But even the better of the theories never answer the question of contingent existence because of their limited methodology, which excludes-arbitrarily, without reason-a transcendent cause.

For this reason, these fantascienze never get to the root of the problem. They do not answer the question. They beg the question.

As Benedict XVI explained, relying on contingent "Nature" to explain Nature–which all scientific-empirical theories of reality try to do–in an effort to avoid the God question is intellectually disingenuous.

To make "Nature" God so as to avoid the question of God is to latch on to an irrational divinity that "non spiega nulla," does not explain a thing. It does not explain a thing and it is irrational because it relies on contingent being to explain contingent being which, of course, does not explain contingent being.

Until the scientist learns to give thanks, he will never get to the answer of contingent existence.

To confront the reality of our contingent existence means-if we are to use our highest form of thought-that we give thanks, that we be grateful. And this, ultimately, yields to faith, what G. K. Chesterton called "faith in receptiveness," a faith in receptiveness which gives rise to a receptiveness to faith.

One might also note in closing that not only is giving thanks the highest form of thought, and so an absolute essential for speculative or theoretical thought. Giving thanks is also the highest form of action.

Giving thanks is therefore an absolute essential thing for practical thought which leads to action. And the central act of giving thanks, at least when it comes to acknowledgement of our contingent being, is the sacrifice of prayer.

Here, faith also provides an answer. It is called the Eucharist. The Liturgy of the Eucharist-the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass-we should always remember, is nothing other than a giving of thanks. Eucharist, of course, comes from the Greek word εá½Ï‡Î±Ïιστία (eucharistia), which means "thanksgiving."

Ultimately, thanksgiving is not only the proper posture for explaining and responding to the reality of our contingent being. Evidently, it is something intrinsic to God. Jesus, after all, gave thanks the Scriptures reveal and so we remind ourselves in every Mass.

When the Lord gave thanks, not only was he setting an example for us. We ought also recall that, when Jesus gave thanks, it was God giving thanks to God.

—–

Andrew M. Greenwell is an attorney licensed to practice law in Texas, practicing in Corpus Christi, Texas. He is married with three children. He maintains a blog entirely devoted to the natural law called Lex Christianorum. You can contact Andrew at agreenwell@harris-greenwell.com.

—