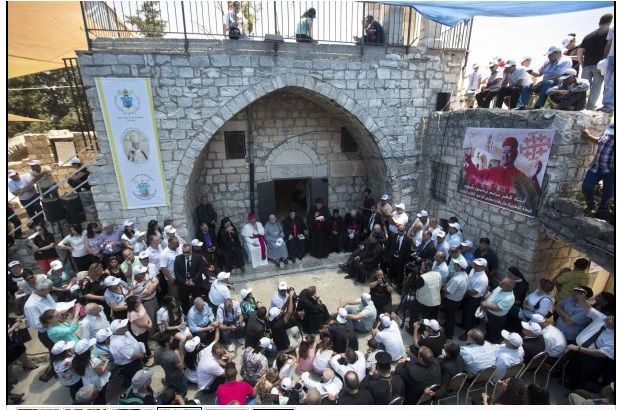

By Associated Press, Updated: Wednesday, May 28, 3:16 PMCAPERNAUM, Israel — The leader of Lebanon’s Maronite Catholic church celebrated an outdoor Mass Wednesday for hundreds of exiled countrymen who are considered traitors by many back home for helping Israel maintain an 18-year occupation of south Lebanon.

Cardinal Bechara Rai had soothing words for the former Lebanese militiamen and their families, who fled their country in 2000, many with just the clothes on their backs, as their Israeli allies withdrew from Lebanon. “Innocence paid the price and you are paying the price because of an international and regional game,” he said, standing behind the altar at sunset, with the biblical Sea of Galilee as a dramatic backdrop. He assured the exiles he was trying to help, adding: “We are following up your suffering with the respective authorities in Lebanon.”

Some of the faithful said they hope the cardinal’s unprecedented pilgrimage to Israel — the first Lebanese religious leader to do so — is a signal they may be able to return home someday. “We are very grateful,” said Vivian Shadid, 25. “We are full of hope that someone is fighting for us, that someone wants us.”

For others, return remains a distant possibility.

The young already speak better Hebrew than Arabic, while some older exiles, especially those who held senior positions in the former South Lebanon Army militia, would face imprisonment if they returned.

Victor Nader, a 55-year-old former senior SLA commander who now works as an electrician, said that “until lots of things change in Lebanon, I wouldn’t think about going back.” He said the cardinal’s visit boosted the morale of the community.

Mariam Younes, 19, was only 5 when her family fled. She speaks accent-free Hebrew and works as a waitress. She misses her extended family in Lebanon, she said, but is concerned about how the community there would receive the exiles. “We are considered traitors in Lebanon,” she said. “And then there’s the bad economic situation” in Lebanon.

Israel invaded Lebanon repeatedly, including in 1982 in an offensive that initially was meant to drive PLO fighters from southern Lebanon.

The war turned into a drawn-out military occupation of parts of the south, where Israel carved out a “security zone” meant to serve as a buffer against cross-border attacks by the Lebanese Hezbollah.

During those years, the South Lebanon Army militia fought alongside Israeli troops against Hezbollah, today the strongest force in Lebanon.

About 3,500 former SLA men and their families still live in Israel, said Shadid, 25, who studies music at Haifa University and said she can’t return because of her father’s military past.

Other exiles either returned to Lebanon over the years, some serving prison sentences before resettling in their villages, or emigrated to the West.

The Mass at Capernaum, site of a biblical fishing village, was a highlight of Rai’s weeklong visit to the Holy Land, which began Sunday in biblical Bethlehem and at times overlapped with a pilgrimage by Pope Francis.

In his sermon, Rai appeared to compare the exile of the militiamen to that of another group of Maronite Christians he met earlier in the day — former residents of the village of Kufr Birim, who were uprooted by Israeli troops in the war over Israel’s 1948 creation.

“This evening is for the displaced, people who lost their homes,” he said.

Rai has come under criticism at home for visiting Israel. Lebanon and Israel remain formally at war and Lebanon bars its citizens from visiting Israel, though Maronite clerics tending to their flock south of the border are exempt.

The residents of Kufr Birim and their descendants have wrangled with Israel’s governments for the past 66 years to allow them to return, using prayer, protests and court challenges in their campaign.

The cardinal told them he would try to harness the help of the Vatican and send a letter to the pope. “The only way is through the Vatican, because we cannot deal with the state,” he said, referring to Israel.

The exodus from the village took place in November 1948, six months after Israel’s founding. At the time, Israeli troops told more than 1,000 residents they had to leave for security reasons, but would be allowed to return after two weeks, residents said.

Israel didn’t keep its word and the Defense Ministry later ignored a Supreme Court ruling allowing residents of Kufr Birim and another Christian village to return home.

Instead, the military destroyed Kufr Birim in 1953 as part of an attempt to create a “security belt” without Arabs near the border with Lebanon, Israeli journalist Danny Rubinstein said.

Many of the villagers now live in Jish, a community three miles (five kilometers) from Kufr Birim.

Only the church and a one-room village school remain intact, but villagers celebrate weddings and bury their dead in Kufr Birim.

For the past 10 months, activists have maintained a steady presence, sleeping in tents pitched in the school. They have cleared weeds from village paths and affixed photos of the original owners to house walls still left standing.

The cardinal’s visit “can help” with the religious side of things, activist Saher Geries said. “But politically, what we are doing now is going to advance” the issue of return, he added.

___

Associated Press writer Areej Hazboun contributed to this report.

Copyright 2014 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.