As of 2010, there were at least 250,000 foreign domestic workers in Lebanon and an estimated 2.1 million domestic workers in all the Middle East—though that approximation may only be half the actual amount, as many aren’t documented. Many of these women work a reasonable number of hours, generate an income that wouldn’t have been possible in their own country, send that money back home to families, and create a home for themselves in their adopted country, as Birtukan has done. The housework and child care they take on allows local women leisure time and to pursue professional careers more freely.

Yet many foreign domestic workers are horribly taken advantage of. Many are made to work seven days a week, locked inside the homes in which they work, their passports confiscated to discourage escape. Often, they are lied to by the dodgy businesses that facilitate their travel abroad, promised salaries and working conditions that never materialize.

Then, there are cases of physical and mental abuse: rape, forced servitude, regular beatings, the list goes on. One human rights worker told me she had heard of a case where a domestic worker was locked to a radiator when her employers fled Lebanon during the 2006 war. In 2008, Human Rights Watch said that domestic workers were dying at a rate of more than one per week in Lebanon. Only 14 of these deaths were due to health issues, meaning that the vast remainder were either homicides, suicides, or even failed escape attempts.

In Lebanese society, the idea that domestic workers are property is pervasive. The human rights workers and activists interviewed for this story all spoke of the power imbalance between employee and employer as a major part of the problem

When women travel to Lebanon, or other countries like Saudia Arabia, Kuwait, and Qatar, for domestic work, the employer controls the work visa through a system known as kafala, or sponsorship. This is also the policy for foreign laborers in other sectors, like construction. Originally, kafala was part of the tradition of hospitality toward foreigners in the Middle East, when an employer took responsibility for the well-being of a foreigner. Now it is a major contributor to worker exploitation. The employer holds all the power, and the employee has zero options. If a foreign employee complains about work conditions, the employer can threaten deportation. And employees can’t leave their employers for better work opportunities since their visas are tied to their employers. They aren’t even allowed to leave the country without permission.

The employer may turn out to be a good person. But relying on a stranger’s kindness in the absence of legal protection is far from failsafe.

When these women run away from abusive situations and their embassies don’t provide assistance, as is often the case for Ethiopians, they fall through the gaps of international migration. They are without passports, away from their home countries—yet they are not refugees and so cannot turn to that part of international law for protection.

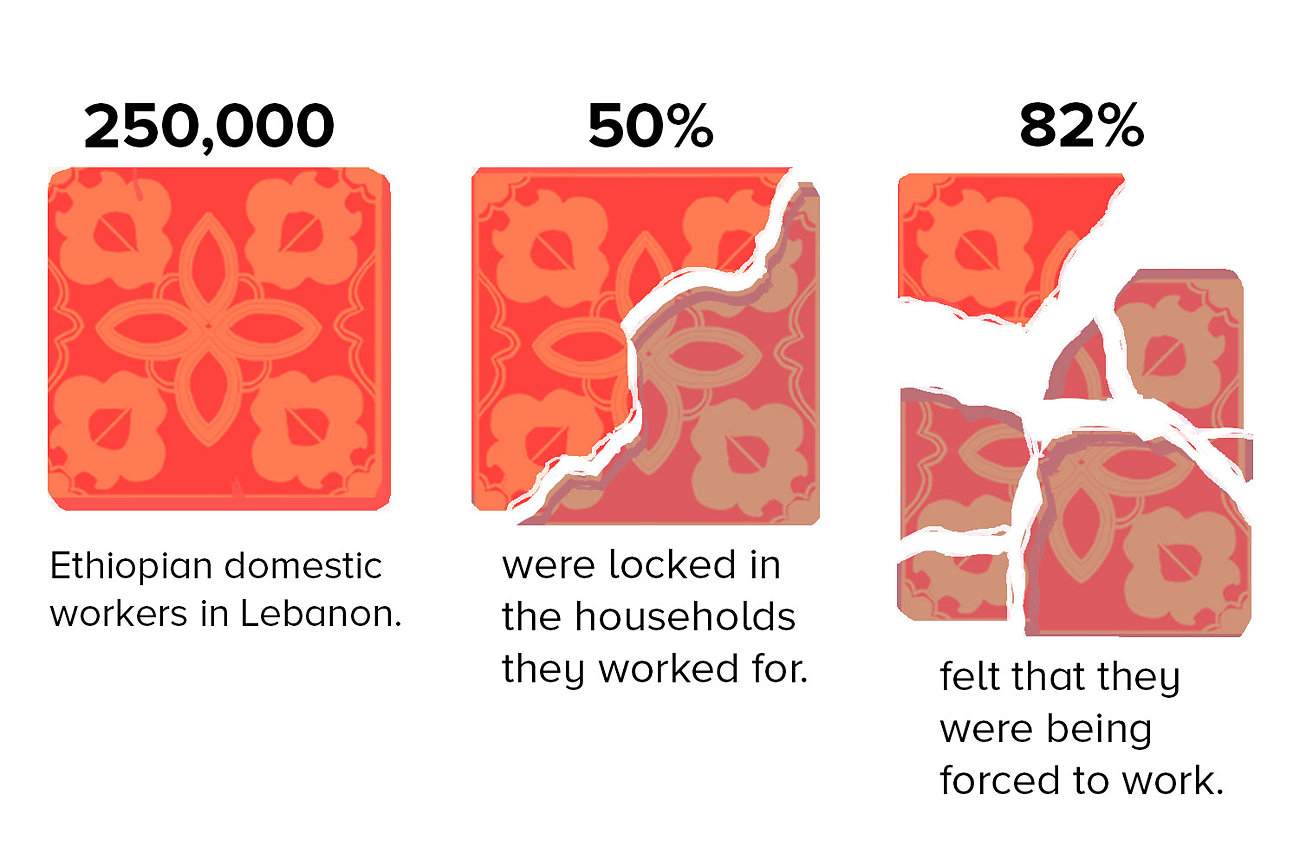

Of the 165 migrant domestic workers interviewed for a survey conducted by KAFA, a Lebanese feminist civil society organization, none had knowledge of the kafala system prior to traveling to Lebanon for domestic work. Over half were paid less than they were promised in their home country, and 82 percent felt that they were forced to work. About 77 percent were made to work more than 14 hours a day. Half were locked inside their homes. The vast majority was asked to give up their identification papers, and 8 percent reported being sexually abused.

“The whole recruitment is exploitation. The recruiters know very well the situation in Lebanon, and they are hiding it,” says Ghada Jabbour, co-founder of KAFA and head of the group’s exploitation and trafficking unit."

That’s where the union, for which Birtukan serves as the Ethiopian women’s leader, hopes to come in. Announced officially last December, the union is an effort to give legal protection to these women, and also, perhaps just as importantly, provide them with a sense of community. It hopes to encourage Lebanese employers to consider these women not as property but as employees who deserve vacations, a say over who they’ll work for, and minimum wage.

Now, the domestic workers union is focused on increasing its ability to help women in vulnerable situations and reaching out to new members. News of the union spreads by word of mouth at places where domestic workers congregate on their days off, like churches, but that’s only if a day off is allowed by employers.

“Domestic workers should have a voice, and this cannot be done by charity or on an individual basis,” says Mustapha Said, senior specialist in workers’ activities for the International Labor Organization in Lebanon. “One of our arguments is that each one of these women is isolated in the household, kept alone, and doesn’t know the language, the laws, and that makes them more isolated, fragile, and exploited. So having a union is for the sake of Lebanon to be seen as a country that respects human rights. It’s also for the employers themselves because it will recognize this profession. We cannot any longer use the excuse that this is not work.”

One of the major demands of the union and NGOs that work on this issue is that the kafala system has to go, that it’s one of the major stumbling blocks when it comes to shielding these women from potential abuse. Another problem is that domestic workers are now excluded from Lebanon’s labor law, which means, technically, they aren’t allowed to have a labor union. I tried for two weeks to no avail to schedule an interview with a Lebanese official at the Ministry of Labor to talk about how the government will respond to the union’s demands. So far, the ministry hasn’t recognized the union. When I finally get Labor Minister Sejaan Azzi on the phone, he declines to answer my questions. "We have nothing new to discuss about this issue," he says.

Human rights advocates say little progress has come from the Lebanese government. It did create a standard contract for domestic workers in 2011, but even that has major gaps. There is no minimum wage, for example, and it’s very difficult for domestic workers to get out of an undesirable contract. While Lebanon voted for a landmark ILO convention in 2011 that spelled out the rights of domestic workers, local law remains far short of what that agreement stipulates.

Castro Abdullah, head of the National Federation of Workers and Employees Trade Unions in Lebanon (FENASOL), is one of the key players responsible for the union’s existence. He’s a serious fellow, large and seemingly staid, but clearly passionate about helping these foreign women who come to his country hoping for a better life. His office is in a poor part of Beirut—stark and plain, adorned only by a few Lebanese flags and some books. Castro tirelessly works day and night, and the three times I visit his office, there’s a string of domestic workers coming in and out asking for immigration or legal assistance.

FENASOL has a long history of standing up for foreigners, originally Armenians and Kurds. Castro says that he’s ashamed of the abuse of domestic workers in his country and that the Ministry of Labor’s response to this issue has bordered on racism. When women first come for domestic work, he says, “They don’t know anything about Lebanon. They don’t know the language. They are beaten, abused. We started to think how can we solve this problem and help these women get their rights.”

Castro sees the union as a safe place for women who are abused and as an advocacy group that can interact with the police on their behalf. “There are women raped, and they have nowhere to go,” he says. “There is no system in place to look after these women.”

Birtukan lives in a humble, though nicely decorated apartment tucked in a back alleyway of a poor Beirut neighborhood. Her bedroom is full of photos of her two sons and late sister. She says her husband abandoned her 15 years ago, leaving her to support their two young boys. The desire to provide an education and better future for her children, now both college students in Ethiopia, is what drove her to look for work overseas at age 23.

“Maybe you can find work in Ethiopia, but your salary is not enough for a family,” she explains to me in Arabic. “It is enough so that you can just eat and buy clothes. There is no saving anything in a bank, and, especially if you don’t have an education, then there is no work.”

Brokers who work in rural areas, villages with minimal electricity and primary schools at most, try to entice young women to travel abroad by showing them a large house that an older woman who had worked in the Middle East was able to buy for her family. These young women may see an older neighbor who has returned from the Middle East wearing nice clothing that they could never dream of owning. Of the dozen or so Ethiopian woman I spoke with who worked as domestic workers in the Middle East, all told me they had traveled abroad on their own volition, about half against the will of their parents. Women often go into debt to pay the brokers who are arranging their travel overseas, making them even more vulnerable.

“The worker is asked to pay the ticket. Some people have to borrow only a few hundred dollars and others a few thousand dollars. It’s really a huge amount for them,” Ghada from KAFA says. “So they have to work off this debt in Lebanon. Even if they are living in an abusive situation, they will accept it because they have this debt. Their consent is really coerced.”

When I ask Birtukan and others why women still travel to the Middle East for domestic work when they know there is potential for abuse, the answer is always the same: Every woman believes that she will be one of the lucky ones.

“They are only thinking to find work,” Birtukan says to me. “But this is normal,” she adds. “I mean, look at you. You traveled here for work, and you don’t know, maybe there will be an explosion, but you are only here thinking of your work.” She makes a good point.

After several publicized cases of domestic worker abuse and Saudi Arabia’s threat to expel undocumented Ethiopian migrants, the Ethiopian government in fall 2013 placed a ban on its nationals traveling to the Middle East on work visas. Other nations, like Nepal, have enacted similar bans. However, this gave human smuggling space to proliferate.

“There is documented evidence that the ban has been counterproductive. That more people are going through the irregular routes at higher costs and in much more vulnerable conditions,” says Bina Fernandez, author of Migrant Domestic Workers in the Middle East: The Home and The World and a lecturer at the University of Melbourne.

In Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, I meet two sisters (both of whose names have been changed), who worked in the Middle East as domestic workers earning about $150 a month. After returning to Ethiopia and finding no sustainable employment options, they both say they would return to the Middle East if it weren’t for the ban. Their domestic work has earned their family some luxuries like a flat screen TV and better furniture. I sit with them in their majlis, a reception room filled with colorful floor cushions, common in the homes of Muslim Ethiopians.

“I wanted to improve my family’s life,” says Aysha, the younger sister at 21 years old. Aysha traveled abroad when she was only 17, which is technically illegal, but women often fake their identification cards. She says that in Addis Ababa, “girls have an understanding that bad things can happen to them” when they go abroad for domestic work. “But there also are ones who have a good experience so I was having mixed feelings about traveling. I decided that whatever would happen would be my fate.”

If the ban lifts, Aysha says she will return to the Middle East.

I ask Aysha, who worked in Dubai, and the older sister Fatima, who worked in Saudi Arabia, why they don’t try to travel via an illegal route.

“It takes maybe two months, and maybe you will be raped, or maybe you will die,” Fatima answers. “It is girls from the countryside who don’t know any better who travel illegal routes.”

I tell the sisters about the efforts of the union, how it’s trying to change things in Lebanon.

“I am skeptical about that effort,” Aysha responds, “because I don’t think this will work practically on the ground.”

Hiring a domestic worker is relatively affordable in Lebanon—more affordable than sending your children to daycare, for example, which encourages the use of domestic workers as nannies. A “keeping up with the Joneses” attitude also plays a role. If a family’s neighbor has a maid, then that family needs to have one to prove that they are also upper class.

Last year, on Mother’s Day, there was a sale offered by a domestic worker recruitment agency in Beirut, a “special offer” to “indulge” your mom with a housekeeper. That type of blatant disregard for these women’s humanity and their consideration as mere merchandise is on full display when I visit two offices that organize domestic worker recruitment, under the pretense of wanting to hire a maid.

The first is shiny and relatively professional. A painting of a white Siberian tiger and a Christian cross hang in the reception area. A secretary hands me the catalogue of maids that Castro told me about earlier. I flip through images of Ethiopian and Kenyan women, girls in cute clothes with forced smiles, one born in 1994. Another allegedly was born in 1982 but looks like she’s maybe 18 at most. She wears hot pink pants and a lime green shirt bearing a sequined owl. I’m struck by how easy it is to hire a domestic worker. I just show up at the office and pay for her travel, the secretary tells me. “Filipinos are better,” she says. “Ethiopians are a bit stupid. Kenyans are alright, though.”

I speak with the second recruitment agent in the back room of a musty women’s clothing shop run by a Lebanese woman with platinum blonde hair, lash extensions, and a large black fur coat despite the heat. The slightly balding agent sits on a stool in front of me and explains the price differences: Filipinos cost $4,500 to order, Ethiopians $2,000. There are also Nepalese, Sri Lankan, the list goes on. I have to pay Filipinos a higher monthly salary, too, about $300, compared to $150 for Ethiopians.

“You can’t give them a day off, or phone and internet. As soon as you give them a phone, they can run away, and then no one in Lebanon will want them,” the agent explains after handing me a tablet and pen so I don’t have to commit price tags to memory. “As soon as you give her a day off, she’ll get a boyfriend. They all have husbands back at home and boyfriends here. You don’t know what she’s doing with her day when she’s outside your house.”

“If you want an expedited maid,” he goes on to explain, since it can take up to two months to bring a woman to Beirut from her home country, “we have those, too. You have to pay them more, $400 a month, but there are no travel costs. She won’t have her papers, so technically it’s illegal, but don’t worry, the government isn’t enforcing this.” That means these are maids who have run away from previous employers.

There are around 500 licensed agencies in Lebanon, and many more unlicensed, so it’s a lucrative business. “These agencies are tied up with other sorts of businesses, particularly import-export businesses in the Middle East,” explains Bina, the lecturer. “Maybe one is in the business of processing female domestic workers, but is also exporting cattle, or engaged in international money transfers.”

I am told by both recruitment agencies that if I don’t like my maid after three months, I can return her. Often, these returned women are kept in a back room of the recruitment agency and not allowed to leave. Frequently they are beaten, human rights workers tell me. Then they are given to another family and told they must work. “She is kept until someone else tries to recruit her, so it’s forced labor,” says Roula Hamati, research and advocacy officer at the human rights group Insan Association.

Hicham Al Bourji, president of the Syndicate of the Owners of the House Workers Recruitment Agencies in Lebanon, acknowledges that the maids recruited by such agencies are sometimes abused. But, he tells me, the country bans on Middle East work visas are only promoting such abuses as these bans just push the process further underground. He also blames the slow Lebanese legal system for not passing laws to protect these women.

Though Hicham says he favors legal protections for domestic workers, his tone changes when I bring up the union currently fighting for such protections. “If I go to any country, I have to respect the rules, even if they are right or if they are wrong,” he says. “The rules in our country say they are not allowed to be in a union. Maybe it’s stupid, but this is the rule.”

One afternoon in FENASOL’s office, I ask Birtukan to tell me the most compelling stories she has heard about Ethiopian domestic workers in Lebanon. She sits for a moment and looks at the ground before responding definitively, “Ameera.” (This name has also been changed for her protection, as have all of the following.)

Ameera is a young woman who came to Lebanon via Sudan five years ago, Birtukan explains. After working as a maid for two years, Ameera fled when it became clear her employers did not intend to allow her to return home at the end of her contract—a common complaint among domestic workers.

Birtukan and I go hunting for Ameera, who Birtukan heard was staying with another Ethiopian woman in a suburb on the outskirts of Beirut, where trendy H&M billboards have been replaced by ones celebrating bearded Hezbollah leaders. Finally we find the place. Wallpaper is pasted to the wide glass storefront so the outside world can’t peek in, but despite the lack of natural light, the Ethiopian women inside are laughing and joyous. The head of the home, tiny Fauzia, continuously makes injera, Ethiopian spongy bread, over a portable stovetop, tossing each sticky, steaming piece onto a table, where another woman then bags it up and places it on a tablecloth on the floor alongside dozens of other injera packages ready to sell. In the room’s corner, sleeps baby Amin, the 3-week-old son of Ameera. Amin’s father is a Syrian man who abandoned Ameera after she became pregnant. Ameera doesn’t know if the father is still in Lebanon, or even if he’s alive at all. She can’t travel back to Ethiopia because her son can’t travel without his father’s permission. She is very thin and wears a tightly wound blue hijab.

Ameera took the position in Lebanon after her sister had returned from domestic work in Beirut. “I saw how my sister helped the family, and I wanted to do the same,” she says with an earnest truthfulness.

I ask Ameera if she was afraid to travel to a new country when she first arrived to Lebanon, and she tells me emphatically that she was not. She had a plan. “I wanted to work for two years and then go back to my home, but my sponsor was bad so I ran away.”

Ameera says she was locked indoors at all times and made to work. She had to take care of seven kids and was made to look after the mother-in-law’s house as well, never with a day off. When she tried to send her $150 monthly salary back to her family in Ethiopia, her sponsor wouldn’t allow it. In fact, she even tried to leave the abusive situation after a few weeks by contacting her agency to tell them it wasn’t working out with the family. They told her, tough luck.

“After two years, when my contract was finishing, I asked if I can buy a bag to travel back to Ethiopia. They didn’t let me buy this bag,” she tells me. It became alarmingly evident that her employer was not going to allow her to return home. So when the family was in the living room, she slipped out the front door with nothing but the clothes on her back. Like the other women in this store-turned-refuge, she escaped without her residency permit or her passport.

Then she met Amin’s father, and now she and Amin are living here with the other women. They are a sisterhood thrown together out of need for communal support. They come from different backgrounds in Ethiopia. Ameera is Muslim, while another has a photo of a resurrected Jesus Christ as her phone background. But these differences don’t seem to matter.

If the domestic workers union increased its capacity to help more women and became an officially recognized organization in Lebanon, these women and others like them could use the union to obtain new passports or get their old ones returned. They would even be able to ask the union for legal assistance in the event that their employers abuse them. That is a future for which Birtukan hopes and fights.

Illustrations by Jean Wei