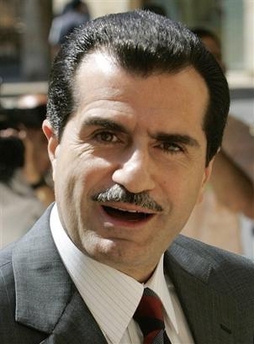

BY ‘He didn’t look the part of the bravest newspaperman in the Middle East. But after he was assassinated at the age of 48 this week in a car bombing that obliterated his Range Rover as he traveled to work in Beirut, it’s clear that’s exactly what he was’ For a scribe, Gebran Tueni was shockingly high mannered. In his dapper suits, crisp shirts and designer ties, wearing a thin moustache that was always immaculately trimmed, he seemed to belong in a gentleman’s club, not a newsroom. He didn’t look the part of the bravest newspaperman in the Middle East. But after he was assassinated at the age of 48 this week in a car bombing that obliterated his Range Rover as he traveled to work in Beirut, it’s clear that’s exactly what he was. Many Arab journalists are fearless when it comes to criticizing Israel or the United States. None other has written so passionately-and in the face of such peril-in support of freedom against Arab dictatorships.

BY ‘He didn’t look the part of the bravest newspaperman in the Middle East. But after he was assassinated at the age of 48 this week in a car bombing that obliterated his Range Rover as he traveled to work in Beirut, it’s clear that’s exactly what he was’ For a scribe, Gebran Tueni was shockingly high mannered. In his dapper suits, crisp shirts and designer ties, wearing a thin moustache that was always immaculately trimmed, he seemed to belong in a gentleman’s club, not a newsroom. He didn’t look the part of the bravest newspaperman in the Middle East. But after he was assassinated at the age of 48 this week in a car bombing that obliterated his Range Rover as he traveled to work in Beirut, it’s clear that’s exactly what he was. Many Arab journalists are fearless when it comes to criticizing Israel or the United States. None other has written so passionately-and in the face of such peril-in support of freedom against Arab dictatorships.

In early 2000, a few months after Tueni took the helm ofAn Nahar, one of the Arab world’s most respected dailies since his grandfather and namesake founded it in 1933, I went to see him at the newspaper’s editorial offices, then in Hamra Street. He was a young writer when I had first encountered him there in some of the darkest days of the Civil War, but 17 years later he was bursting with hope. As we sipped Turkish coffee, he articulated a coherent vision of a new Middle East free of authoritarian regimes, well before the Bush Administration discovered that democracy could be a good thing for the Arab countries.

"We can’t be ruled by one-man regimes anymore," he said. "The Arabs went down, down, down for a half century, so a new generation has to re-think the Middle East. We could achieve anything. We have the people, the minds, the money." A few days earlier, Tueni had dared to pen an open letter in An Nahar to Bashar Assad, who was being groomed to succeed his father Hafez as the unelected leader of Syria. Though addressing him cordially with "an open heart" as "Dr. Bashar," Tueni’s words were stinging. He told him that the Lebanese "detest" and "reject" Syria’s occupation and asked that he allow Lebanon to be free. He had no illusions that the letter would prompt Syria to withdraw its military and intelligence apparatus. But, Tueni told me then, somebody had to break the fear barrier and speak out for freedom. By doing so, Tueni was paving the way for others to join the challenge to Assad’s regime, eventually including Lebanon’s billionaire tycoon turned Prime Minister, Rafiq Hariri.

Tueni thought of Bashar as a "new generation" leader and had hopes that Syria would finally loosen up when Assad Sr. suddenly died in June 2000. But he was disappointed as the months and years passed. Instead of backing Lebanon’s democratic forces, he complained, the younger Assad aligned himself with Lebanese President Emile Lahoud, a former army commander known for his subservience to Damascus, and Sheik Hassan Nasrallah, leader of the Iranian-backed militant Shi’ite group, Hizballah.

Widespread fury toward the Syrian regime over Hariri’s assassination last February changed everything. Tueni went for broke, turningAn Nahar into the mouthpiece of the Cedar Revolution that took over Beirut’s streets demanding that Syrian troops leave the country. He addressed the historic demonstration of two million Lebanese that filled Martyrs’ Square on March 14. Little more than a month later, Syrian solders ended their 29-year stay in Lebanon.

For an ambitious visionary like Tueni, the Syrian exit, the "miracle" that it was, was not the end but the beginning. In May, aligned with Hariri’s son, Saad, he won a seat in parliament, following in the footsteps of his father Ghassan, an elder statesman and doyen of Lebanese journalism. Tueni liked the idea of having the opportunity to legislate change, but there was no question that runningAn Nahar would remain his day job. He sought to harness the energy of the young protesters to scrap Lebanon’s age-old sectarian system in favor of one that allowed all Lebanese to participate fully in the country’s future. "We can speak the language of the new century," he told me at the height of the demonstrations. "But we can’t build a new Lebanon with old ideas." An immediate problem was that Syria’s hand was still felt in Lebanon, thanks to the infrastructure of agents, informants and black operations that it had used to manipulate the country over the years. A wave of bombings occurred, then more assassinations. All were widely blamed on Syria or its Lebanese supporters, but as with the Hariri killing, the Syrians denied any involvement. Tueni learned that he was on the top of a hit list and started taking precautions, like switching cars every other day. In June came the anticipated explosion, targeting not Tueni but his star columnist Samir Kassir.

By then, it was no more "Dr. Bashar." He referred to Assad’s "tyrannical" and "despotic" regime, and increasingly mocked it with sarcasm. Like other opponents, he went abroad for awhile to escape the threatening atmosphere, but his criticism of Syria continued in An Nahar’s pages. On the last Monday evening of his life, shortly after his return to Beirut, he invited me over to An Nahar’s gleaming new office building in Beirut’s reconstructed downtown. As we sat in his stylish corner office, which overlooked Martyrs’ Square, he was hopeful as usual about the future. He believed that the United Nation’s investigation into Hariri’s killing, which issued a second interim report last week, would eventually expose the Syrian regime’s involvement. He waved a copy of the day’s An Nahar, which front-paged a story on mass graves discovered at the former Syrian military intelligence HQ in Lebanon. In his last, acerbic editorial three days later, he would blame the Syrian regime for the "crime against humanity," call for an international tribunal"

Tueni’s eyes momentarily froze at the suggestion that his dogged pursuit was putting him at even greater risk. "That’s what journalists have to do, get out the truth, isn’t it?" he asked. He was trying to convince himself that the assassins wouldn’t come looking for him in the end. He explained that the Syrians knew that he had been honest and consistent in his criticism, that he was no political opportunist. "Even among people in that regime, there is some kind of honor," he reassured me. That was Tueni’s optimism for you. "No tears," said his 79-year-old father, who went to An Nahar’s newsroom after his son’s murder to console the weeping staff members. "Gebran is not dead." Tueni’s dream of a free Lebanon, in other words, lives on.