MODERN Syria is dead. Russia’s intervention into the bloody four-year conflict cements that reality. Now U.S. policymakers must plan for what comes next. And it’s not pretty.

Officially, the Russians say they entered Syria to fight the radical Islamic State. But they come at the invitation of Syria’s besieged president, Bashar al-Assad, and Russian bombing runs targeting U.S.-backed rebel forces underscore the fact that Russian President Vladimir Putin’s intervention is really about propping up the Assad regime, Moscow’s only ally in the region.

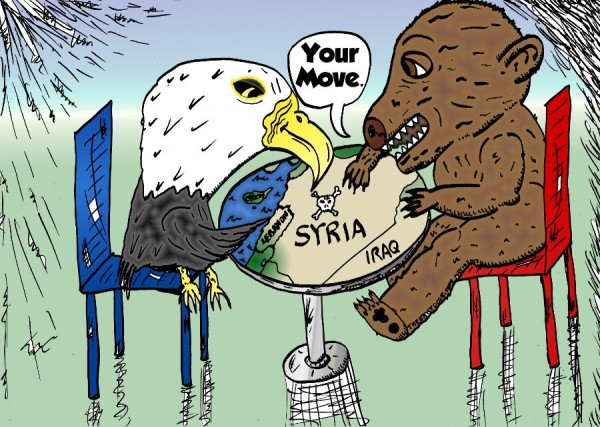

That pits Washington, D.C., and Moscow in a proxy war reminiscent of conflicts in Southeast Asia and Africa during the Cold War, and it limits the West’s military options in supporting the anti-Assad rebellion and forcing Assad to step down.

All of this effectively means modern Syria has been relegated to the history books. The country has splintered and no amount of diplomatic duct tape is ever going to lash it back together again. The idea that Assad might still be convinced to step down and that all factions will come together and sing Kumbaya is a fantasy.

More than half of Syria’s prewar population has been driven from their homes. Millions languish in refugee camps in neighboring countries. Tens of thousands more are in a desperate scramble to reach Europe. And 30,000 foreign fighters now battle alongside the Islamic State.

There are 29 armed factions engaged in the fighting. Each controls its own little piece of turf. Even before Russia’s intervention, the prospect of a united Syria re-emerging was unlikely at best.

Just look at Syria’s neighbor Lebanon. Four decades after its own civil war erupted — with many of the same factions as in Syria and the same array of regional players stoking the flames — Lebanon still teeters on the brink of collapse.

In his U.N. speech, President Obama warned against “dangerous currents pulling us back into a darker, disordered world.”

The reality is that the U.S. can swim so only hard against the tide. We should have learned that in Iraq and Egypt; both countries are in far worse shape today than before American policy fueled a decade of conflict in one and revolution, counterrevolution and coup in the other.

When it comes to Syria, Western meddling after World War I created conditions that set the stage for today’s chaos. Syria and its neighbors were created when the European powers drew a series of largely arbitrary lines in the sand. Ethnic and religious communities were divided into unnatural entities the big powers declared to be nations. Those lines in the sand are today being erased with blood.

Russian intervention has now raised the stakes: A regional tragedy could be transformed into a new flashpoint between Washington and Moscow.

To avoid a worst-case scenario, American policymakers need to avoid hype about the Russian bear flexing its muscles and acknowledge Russia’s legitimate geopolitical interests in the region.

The U.S. may not have liked Russia’s annexation of Crimea last year, but it was a natural move. As Ukraine tilted West, Putin acted to protect Russia’s only warm-water port and prevent a Western incursion into what he sees as his legitimate sphere of influence. Ditto the Syrian intervention.

At stake is the Russian navy’s access to the Syrian port of Tartus, 60 miles from where Russian troops are busy reinforcing the airport to handle his bombers. If he loses Assad, Putin would likely lose access to his Navy’s front door on the Mediterranean. And by launching the first Russian combat missions outside the Soviet bloc in 70 years, he protects his toehold in the Middle East and in the process cozies up to Assad’s other ally, Iran, the main regional rival to Washington’s Saudi ally.

Safeguard his navy’s Mediterranean presence. Ally with Iran. Checkmate the U.S. That’s called realpolitik.

Granted, it’s not likely to win Putin any friends in a region where he already has few. Headlines across the Arab world highlight the civilians, including children, reportedly killed by Russian bombs — not surprising given that Putin has effectively taken Shiite Iran’s side in its Cold War with the region’s Sunni Arab majority.

Yet there is a grudging respect in a region exhausted by the Syrian carnage. “Russia has a plan for Syria,” wrote a columnist in Lebanon’s Daily Star last week, “while the United States does not.”

For U.S. policymakers, it’s now about the long game: Lead a comprehensive Western response to the humanitarian crisis; confine and crush the Islamic State; acknowledge Russia’s legitimate interests in the region and guard against being sucked into a military confrontation with Moscow; avoid putting boots on the ground in a conflict where there can be no victory; and accept the fact that Washington cannot always redirect the dangerous currents of history.