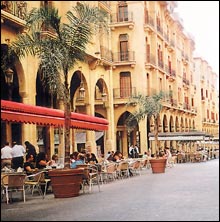

BEIRUT, 21 March (IRIN) – Beirut’s impressive downtown district reflects much of the wealth and development that Lebanon has enjoyed since the end of the civil war in 1990. But a few minutes’ drive to the capital’s southern and northern fringes reveals a vastly different reality, featuring extreme poverty and underdevelopment. Residents and NGOs working to alleviate poverty put much of the blame for the shabby condition of the suburbs on government inaction. "We’re second class citizens," said Youssef Hassan, a 48 year-old resident of the southern suburb of Hay al-Selom. "Officials forget we exist below the poverty line."

BEIRUT, 21 March (IRIN) – Beirut’s impressive downtown district reflects much of the wealth and development that Lebanon has enjoyed since the end of the civil war in 1990. But a few minutes’ drive to the capital’s southern and northern fringes reveals a vastly different reality, featuring extreme poverty and underdevelopment. Residents and NGOs working to alleviate poverty put much of the blame for the shabby condition of the suburbs on government inaction. "We’re second class citizens," said Youssef Hassan, a 48 year-old resident of the southern suburb of Hay al-Selom. "Officials forget we exist below the poverty line."

"I get about 300,000 Lebanese pounds a month from driving people around," he said. "It barely covers the rent of the car I’m using and basic needs, like food. We have to buy clothes second-hand – if not third-hand." Hay al-Selom and the suburb of Nabaa, about a 15-minute drive north of Beirut’s city centre, constitute the capital’s two main poverty belts, according to a December 2005 study funded by the World Bank. The study was conducted by the Lebanese Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR), set up by the government in 1977. The survey, the aim of which was to identify deprived areas for future development, classifies these two suburbs as "the most deprived around Beirut." It goes on to note that poverty on the outskirts of the capital was "one of the key issues that consecutive governments have failed to resolve." While relatively affluent neighbourhoods nearby have seen a modicum of reconstruction and development in the last decade, including road construction, wastewater treatment and electricity projects, such development has eluded the impoverished areas on the capital’s periphery. As a result, the existing situation has led to other poverty-related crises, including unchecked demographic growth, inadequate housing, weak socio-economic conditions and health problems. "The lack of an interactive role by the state in these areas has led to many problems," said Ali Bazzi, head of the Social Affairs Ministry’s centre in Hay al-Selom. "Sewage pipes pollute the nearby river and the electricity network doesn’t reach all the houses." Residents also complain of frequent power outages and unsafe drinking water. "We treat many cases of diarrhoea in our clinic here," said Bazzi. He went on to explain that the centre provided basic health and social services, but that its resources were not enough to cover the entire area, which he estimates is home to about 250,000 people. "If it wasn’t for the work of volunteers, we wouldn’t have been able to offer half of the services we now provide," Bazzi said. He added that government officials were unconcerned with the plight of Hay al-Selom residents because most of them are migrants from rural areas. "As migrants, they don’t have the right to vote in municipal and parliamentary elections," said Bazzi. "Officials tend to offer services to voters in their constituencies." According to the CDR study, there are only 350 registered voters in Hay al-Selom. NGOs, therefore, are hoping to perform the role traditionally assigned to the state in these areas. Cynthia Aoun, press officer of Social Movement, a local NGO devoted to poverty alleviation in the capital, said that aid agencies and political parties were taking on most of the burden in catering to the needs of area residents. Aoun’s NGO, which has worked in Lebanon for over 40 years, provides social help for Beirut’s poor, focussing mainly on children and education. "But the work of NGOs cannot – and should not – replace that of the state," she said, warning that the situation would only worsen in the absence of government participation.