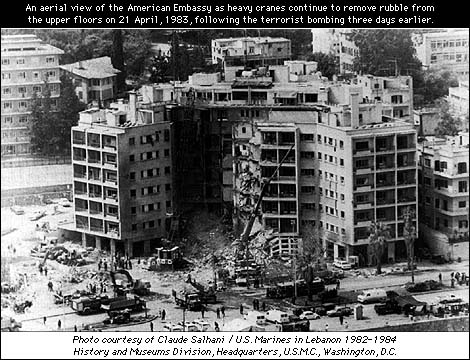

By CLAUDE SALHANI UPI International Editor WASHINGTON, Oct. 19 (UPI) — Quite unlike the invasion of Iraq, the U.S. Marines in Lebanon came in peace — and at the request of the Lebanese government. This Sunday, Oct. 23, will mark the 22nd anniversary of the bombing of the Marine barracks in Beirut where 241 U.S. servicemen, mostly Marines, lost their lives. At approximately 6:22 a.m. on Sunday, Oct. 23, 1983, a lone terrorist driving a yellow Mercedes-Benz stake-bed truck loaded with explosives accelerated through the public parking lot south of the 24th Marine Amphibious Unit Battalion Landing Team headquarters building, detonating about 12,000 pounds of hexogen. According to the official Department of Defense commission report, the force of the explosion ripped the building from its foundation. The building then imploded upon itself and almost all of the occupants were crushed or trapped inside the wreckage.

By CLAUDE SALHANI UPI International Editor WASHINGTON, Oct. 19 (UPI) — Quite unlike the invasion of Iraq, the U.S. Marines in Lebanon came in peace — and at the request of the Lebanese government. This Sunday, Oct. 23, will mark the 22nd anniversary of the bombing of the Marine barracks in Beirut where 241 U.S. servicemen, mostly Marines, lost their lives. At approximately 6:22 a.m. on Sunday, Oct. 23, 1983, a lone terrorist driving a yellow Mercedes-Benz stake-bed truck loaded with explosives accelerated through the public parking lot south of the 24th Marine Amphibious Unit Battalion Landing Team headquarters building, detonating about 12,000 pounds of hexogen. According to the official Department of Defense commission report, the force of the explosion ripped the building from its foundation. The building then imploded upon itself and almost all of the occupants were crushed or trapped inside the wreckage.

"It was one of the largest noises I’ve ever heard in my entire career," said retired Marine Maj. Robert T. Jordan, the 24th MAU public affairs officer at the time of the bombing. Jordan was in his rack in an adjacent building when the explosion split the still morning air and showered him with glass and pulverized concrete. It was also the heaviest loss the Marine Corps suffered in any single day since the battle of Iwo Jima during World War II. A few moments later another suicide bomber rammed his truck into the "Drakkar," a building occupied by French paratroopers. Fifty-eight French soldiers perished in this attack. The Marines, the French, the Italian and the Brits had come in peace — to help secure peace in Lebanon.

First some history: the Lebanese civil war that had started in 1975 had entered a new phase. It was more of an undeclared lull, with Christians in east Beirut and the Muslim-Leftist-Palestinian alliance on the other side in West Beirut, each holding their ground. Beirut was living through an extended cease-fire. It was as though the combatants had grown tired of fighting. In addition to the dozens of armed militias, Palestinian commandos and Syrian regular forces controlled large swaths of the country.

On June 3, 1982, Israel’s ambassador to Britain, Sholmo Argov, was shot as he left a dinner reception at London’s Dorchester Hotel. The attack was carried out by three members of Abu Nidal’s group, a renegade unit at odds with the Palestine Liberation Organization chief, Yasser Arafat. Argov was hit in the head, but survived.

Two days later, on June 5, Israel launched Operation Peace for Galilee — a full-scale invasion of Lebanon. The invasion was initially designed to push back Palestinian forces operating in south Lebanon, north of the Litani River, thus placing their heavy artillery out of range of the Jewish settlements in the northern Galilee. However, then Defense Minister Ariel Sharon saw an opportunity to suppress the PLO once and for all, and pushed his troops all the way to Beirut.

Israeli forces, supported by their Lebanese Christian allies, laid siege to West Beirut for a grueling 88 days, pounding the city with heavy artillery as well as subjecting it to intense aerial and naval bombardments.

Eventually Philip Habib, President Reagan’s special envoy to the Middle East, negotiated a cease-fire. The Palestinians agreed to leave Lebanon for new exiles in Tunisia, Algeria, Yemen and other countries so long as an international military force could protect the Palestinians who remained behind.

This saw the creation of the Multinational Force, consisting of U.S. Marines, French and Italian troops (the Brits later sent a token force). On Sunday, Aug. 21, Arafat, protected by French troops left Lebanon from Beirut’s port, heading for Tunis. Over the next 12 days, 14,383 Palestinian commandos and Syria soldiers, as well as 644 women and children were dispersed around the Arab world.

Shortly after the departure of Arafat and the PLO, Reagan declared a premature victory and ordered the Marines out. "A job well done," he said.

On the afternoon of Sept. 14, 1982, Bachir Gemayel, Lebanon’s president-elect, was killed by a massive car bomb in an office building in East Beirut. That evening — with the multinational force gone — Christian militias entered the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Chatilla.

Approximately 1,300 people were massacred — mostly Palestinians, but also some Lebanese, Syrians, etc. Afterward, though, many Palestinians disappeared from the Beirut Sports Stadium, where they had been detained. Hundreds of boys and men were trucked away never to appear again. To this day, no one really knows where all the bodies are buried, though apparently a huge number are undoubtedly in the mass grave within the camp. But that’s another story.

After the massacre the Lebanese government asked for the return of the Multinational Force — and they did return. They came in peace.

If mistakes were committed in Lebanon — and they were — blame should not befall the Marines, or the French paras who paid the ultimate price for peace.

The error was due to lack of coherent foreign policy coming from both Washington and Paris, and their unequivocal support of Lebanon’s President Amin Gemayel. That is what lost the hearts and minds of a segment of the Lebanese population the Marines had worked so hard to win.

They had come in peace. Two hundred and forty-one of them never left.

—

(Comments may be sent to Claude@upi.com.)