By Marvine Howe, AUB, as the school is generally known, is still mourning its martyrs from Lebanon

By Marvine Howe, AUB, as the school is generally known, is still mourning its martyrs from Lebanon

Even after the new period of uncertainty, AUB forged ahead with its expansion program. Cranes and workmen are busy at the sites of a new School of Business, an Engineering Laboratory Complex, and a Student Center. Renovations have been carried out on several of the original buildings, are due for completion on the Archeological Museum in January 2006, and are underway on the Medical Center. The AUB School of Nursing celebrated its centennial this summer with plans to develop a full-fledged faculty of nursing, including a doctoral program and research center.

AUB President John Waterbury called 2005 “a year of tragedy and a year of hope” in his commencement address to the 1,688 graduates of 2005—the second largest class in the school’s history. Dr. Waterbury, who has presided over AUB’s revival, declared that his hopes outweighed his fears because “the Lebanese have proved they can, through will power and determination, change situations that had been cause for despair.”

One of the oldest universities in the Middle East, AUB was founded by American missionaries in 1866 as the Syrian Protestant College, an independent institution with a focus on medical studies, chartered by New York State. In 1920 the college was renamed the American University of Beirut, and in 1924, became one of the first coeducational schools in the region. During World War II, AUB’s Hospital was open to combatants on both sides, and the campus served as a relief center.

Traditionally AUB officials tried to stay away from politics, aware of the need to preserve the good will of their Lebanese hosts and American and Arab supporters. But with the Arab-Israeli wars of 1967 and 1973, many students and faculty members openly expressed their anger against the American bias in favor of Israel. At the same time, the U.S. Congress and public reacted with increased hostility toward Arab radicals, and AUB activists in particular. During the 16-year civil war, AUB suffered tremendously; enrollment plummeted, American and Arab funding dried up, and the Lebanese government provided funds for the school to carry on.

A major problem for AUB from 1984 to 1998 was the U.S. government ban on American citizens traveling to Lebanon, which discouraged other foreigners as well. Some American professors used Irish passports to stay on at AUB, while a number of Lebanese Americans traveled on Lebanese passports. American presidents of AUB had to run the school by remote control. In January 1998, Dr. Waterbury, professor of politics and international affairs at Princeton, became the first American president to reside in Beirut since the ban, giving hope to the university community that life had returned to normal in Lebanon.

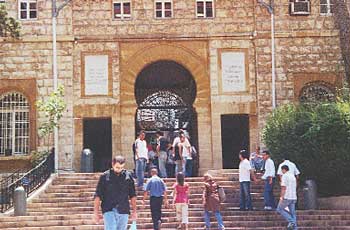

“AUB is still the school of choice in the region, with one of the world’s greatest campuses overlooking the Mediterranean, but many schools in the United States have better infrastructure, classrooms, labs, recreational facilities,” President Waterbury said in a recent interview. He emphasized the need for major works to provide state-of-the-art facilities for teaching and research.

Another wartime casualty was AUB’s traditional diversity. In pre-war days, Dr. Waterbury noted, 50 percent of the students came from around the Arab world, and the faculty had a strong American component. Today, he said, the student body has doubled and stands at 7,000, with 600 full-time faculty members, but 80 percent of the students and 75 percent of the faculty are Lebanese.

Samir Kadi, associate director of development, said that after Sept. 11, “there was a great flow of applicants from the Arab world.” He hoped the school would achieve a ratio of 40 percent foreign to 60 percent Lebanese within a few years.

In an important show of confidence, AUB embarked in 2002 on a campaign to raise $140 million for its development plans. By summer 2005, the university had reached 76 percent of the goal, according to Steve Jeffrey, vice president for development. In the past, AUB raised between $5 million and $6 million a year, mostly from American foundations, alumni and Protestant mission families. This year, according to Jeffrey, that figure has more than doubled to between $14 million and $15 million, with half of the contributions coming from the Arab world. In the critical months following Hariri’s assassination, the United States also provided new support, contributing $2.2 million to AUB’s scholarship fund.

Associate provost Waddah N. Nasr acknowledged that the recent bombings have had a negative impact on recruiting students and faculty abroad, but believed it would be temporary. “Students see in AUB a side of America that contrasts sharply with the prevailing perception of the United States as a dominant power supporting tyrants,” Nasr said. “This is the best face of America: freedom, tolerance, an alternative to the clash of civilizations where people learn together and are free to disagree.”

Meanwhile, AUB is developing its role as a bridge between the United States and the Middle East. In the wake of 9/11, the university launched a program for Understanding Contemporary Islam. Funding came from private American organizations such as the Carnegie Corporation and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. Dr. Abdul Hamid Hallab, head of the program, said 29 Islamic scholars have been sent to teach in American colleges and universities, and 13 of them have been invited to set up programs in Islamic studies.

AUB’s Center of American Studies and Research was inaugurated in June 2003 with a $5 million endowment from Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal of Saudi Arabia. The chair in American Studies was established to honor Edward W. Said, the Palestinian-American scholar who died in September 2003. Said, a member of AUB’s international advisory council, had long stressed the need to teach American culture to Middle Easterners.

The university’s Center for Arab and Middle Eastern Studies, suspended during the civil war, reopened in 1997 with only five students. Since Sept. 11, 2001, however, American interest in Middle Eastern studies has soared, according to the center’s director, John Meloy, who said 50 students are now working for their master’s degree. The center also offers an intensive Arabic-language summer course at six levels; enrollment has grown from 49 in 2001 to 76 this summer, with most of the students American undergraduates.

“AUB really introduced the American system of higher education to the Arab Gulf states during the Lebanese civil war,” said George Khalil Najjar, dean of the business school and vice president for external programs. He recalled how the university had kept scores of professors on its staff with the creation in 1978 of an off-campus program, “loaning” professors to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and other countries of the region.

Now, Dean Najjar stressed, AUB is competing with top American universities like Cornell, Texas A & M, Georgetown and the University of Arizona for the pool of students, faculty members and projects in the Arab world. He cited four advantages that AUB has over its wealthy American competitors: “We know the Middle East and speak the language better than they do. AUB costs a lot less than its U.S. counterparts. We have continuity and are not going away. Also, AUB has brand recognition throughout the region as far as the Bedouin village at the tip of Oman.”

Marvine Howe is the author of Turkey Today: A Nation Divided over Islam’s Revival and the recently published Morocco: The Islamist Awakening and Other Challenges.