By MICHAEL SLACKMAN, BEIRUT, Lebanon Dec. 29 – The roadblocks begin a few miles before Gen. Michel Aoun’s house on a plusvh green hillside dotted with expansive villas. First, two soldiers and concrete barriers stop traffic. Then a maze of concrete blocks slows cars to a crawl. Then three more soldiers. Then a gate, and more guards, and a metal detector. Cellphones are placed in a cabinet and, finally, there he is, General Aoun, leader of the largest Christian bloc in Parliament.

By MICHAEL SLACKMAN, BEIRUT, Lebanon Dec. 29 – The roadblocks begin a few miles before Gen. Michel Aoun’s house on a plusvh green hillside dotted with expansive villas. First, two soldiers and concrete barriers stop traffic. Then a maze of concrete blocks slows cars to a crawl. Then three more soldiers. Then a gate, and more guards, and a metal detector. Cellphones are placed in a cabinet and, finally, there he is, General Aoun, leader of the largest Christian bloc in Parliament.

Clear across the city, out of town and up a winding mountain road, the country’s Druse leader, Walid Jumblatt, is holed up in a medieval castle, protected by soldiers, checkpoints, an army of his own men and a towering metal gate.In fact, most of Lebanon’s chief political and factional leaders are taking cover these days, rarely leaving their well-guarded compounds, fearful they will be killed.

"Nowadays it has become more risky," Mr. Jumblatt said when asked if he ever leaves his mountain fortress. "They have listening devices stronger than the Lebanese Army. They have infiltrated everything."

The "they" Mr. Jumblatt was referring to was whoever has this country on edge, whoever killed the former prime minister and killed or maimed 15 other prominent people this year. People across this city are expecting that someone else will die, wondering only if it will come on New Year’s Eve, or the day after or the day after that.

Many people blame Syria for the attacks – an accusation the Syrians deny. But among the many Lebanese factions that have long jockeyed for power here, people do not trust one another, either. The fear and suspicion flows in many directions.

Beirut is famous, legendary even, for its wild New Year’s Eve celebrations with European-style nightclubs and private parties raging well into New Year’s Day. But not this year, not when many people are mourning more than just the killings. There is a perception among many here that as time has passed, the West, and America in particular, have lost interest in tiny Lebanon, leaving it to twist in the wind as some of its best and brightest are slaughtered.

"We are going to cry," said Salwa Sayegh, a clothing shop owner in the Christian neighborhood of Zalka, when asked what her plans were for New Year’s Eve. "There is nothing good in this country."

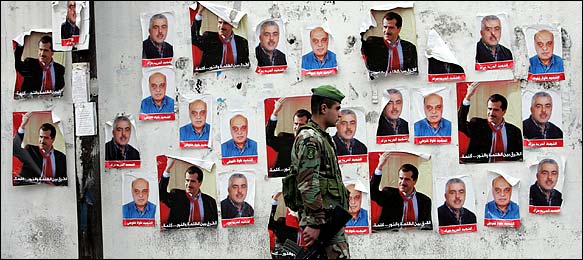

Lebanon, or at least its capital city of Beirut, seems nearly paralyzed. The streets are filled with soldiers, and armored vehicles that belong on a battlefield. Every parking lot attendant is armed with a device that supposedly detects explosive materials. Hotels are barricaded behind concrete barriers and the United Nations offices downtown are now surrounded by huge metal gates.

"Even the youth are not going out as much as before," said Omar Zein, 22, manager of a women’s clothing shop downtown who cranked the music in his boutique up to ear-splitting levels because he was all alone at midday.

The government has effectively stopped functioning. Pro-Syrian ministers have suspended their participation, and the political leaders can hardly get together to discuss the crisis because they are barricaded behind security barriers. "I am one of those who have risk on my life," said General Aoun, who said he spent most of his time meeting people in his well-guarded home.

Mr. Jumblatt said: "We move sometimes. We send messages to each other. We talk on the phone. Tell me, what can we do?"

The fear of another attack has fueled a political crisis, of course, but it has also set off a social crisis, one that has undermined not just the holiday spirit, but a faith in the future.

Paddy Cochrane, 29, a member of one of the most prominent Christian families in Beirut, said it was not that people had lost faith in Lebanon, but that "they are concerned about their future in Lebanon."

There was no giant Christmas tree in the center of the city this Christmas. Many hotels report operating at about 60 percent capacity. Nightclubs and restaurants have canceled many shows, fearful that people will not turn out, and they will be stuck with bills they cannot pay. Many people are scared of being in a crowded place, while others are just sad about all the killings.

"If we have reservations, by 4 or 5 o’clock they call and cancel," said Crystal Abboud, receptionist at Buddha Bar, a massive restaurant and nightclub in the middle of the city. "People are afraid, scared."

For the first time, she said, the bar has had to promote its holiday party with television commercials.

Mr. Cochrane and some friends have been working to keep the party spirit alive as well. At his family’s walled, storybook-style palace, workers built a huge tent in the garden, a three-tiered dance floor, and a cage for a Vegas showgirl, all in preparation for a New Year’s Eve party gamely named "Gardens of Pleasure." He said he was even flying in Ukrainian models to stage a fashion show.

But ticket sales were not as brisk as they had been in the past, and while he said that he did, finally, expect to sell 1,000 of them, many people had expressed anxiety.

"Everyone has the question, ‘What if another bomb goes off?’ " Mr. Cochrane said. "Last year, people wanted to know what was on the menu."