Twitter – it’s everywhere, isn’t it? Well, maybe not, according to one study. Despite being widely known throughout France, with 89 percent of internet users aged 15 or over in the country aware of the micro-blogging social network, just 11 percent have, or once had, a Twitter profile. Moreover, the survey, conducted by Ipsos […]

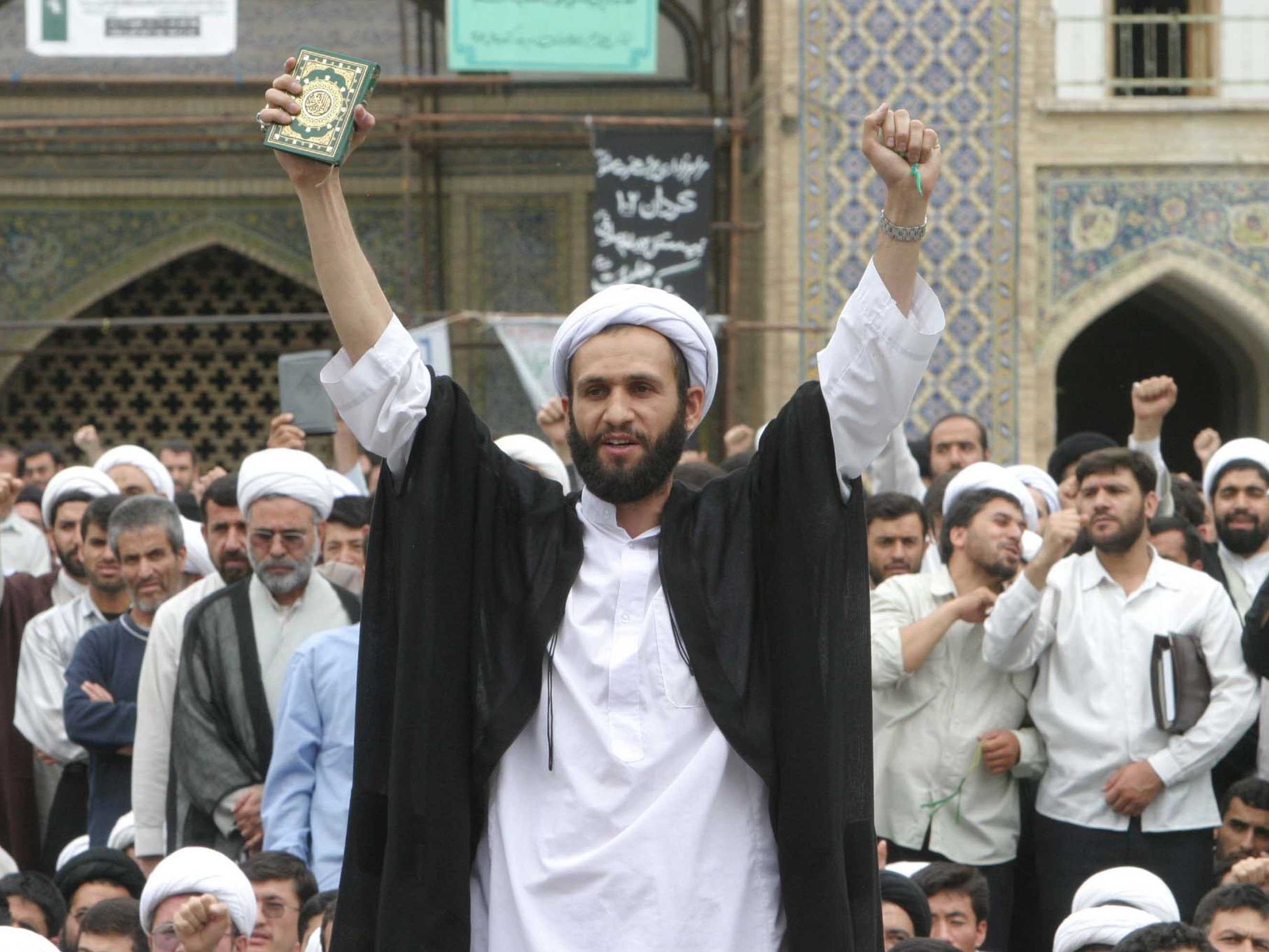

EARLIER this year Iran’s authorities arrested a score of men who, in separate incidents, claimed to be the Mahdi, a sacred figure of Shia Islam, who was “hidden” by God just over a millennium ago and will return some time to conquer evil on earth.

A website based in Qom, Iran’s holiest city, deemed the men “deviants”, “fortune-tellers” and “petty criminals”, who were exploiting credulous Iranians for alms during the Persian new-year holiday, which fell in mid-March.

Many of the fake messiahs were picked up by security men in the courtyard to the mosque in Jamkaran, a village near Qom, whose reputation as the place of the awaited Mahdi’s advent has been popularised nationwide by President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. When he took office in 2005 he gave the mosque $10m.

Iran’s economic doldrums may have helped to cause this surge in people claiming to be mankind’s saviour—and in women saying they were the Mahdi’s wife. “In an open atmosphere where people could criticise the government they would not believe these people,” says an ex-seminarian in Tehran, the capital, noting that most Iranians still get all of their news from state television and state-owned or -sanctioned newspapers.

Last year a seminary expert, Mehdi Ghafari, said that more than 3,000 fake Mahdis were in prison. Mahdi-complexes are common, says a Tehran psychiatrist. “Every month we get someone coming in, convinced he is the Mahdi,” she says. “Once a man was saying such outrageous things and talking about himself in the third person that I couldn’t help laughing. He got angry and told me I had ‘bad hijab’ and was disrespecting the ‘Imam of Time’,” as the Mahdi is known.

It’s just a couple of hours after the AP’s Twitter account was hacked, sending markets into a tizzy with a false report of violence at the White House.

These emails are (usually) a ham-handed bit of “social engineering,” containing some text and a link. The trick is, getting people to click on the link.

If you’ve ever been offered free porn in your inbox, you know the drill: some proportion of dopes who receive the email will click on the link, leading them to a site that may try to install malicious software on their computer.

But we already know, through tidbits offered by the AP itself, how it happened.

First, there was a “phishing” email sent to reporters at the AP:

That reporters at the AP received an “impressively disguised” phishing email speaks to the competence and determination of the attackers. It’s not easy for overseas hackers who are not native speakers of the language used by their targets to write completely convincing emails, for example.

Despite all of the horror, fear, and loss in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombings, people have responded with bravery.

Many people who finished the marathon after the bombings just kept on running to area hospitals to see if they could donate blood or otherwise help.

We’ve found the tweets, images, and stories that document some of the amazing responses to a tragedy.