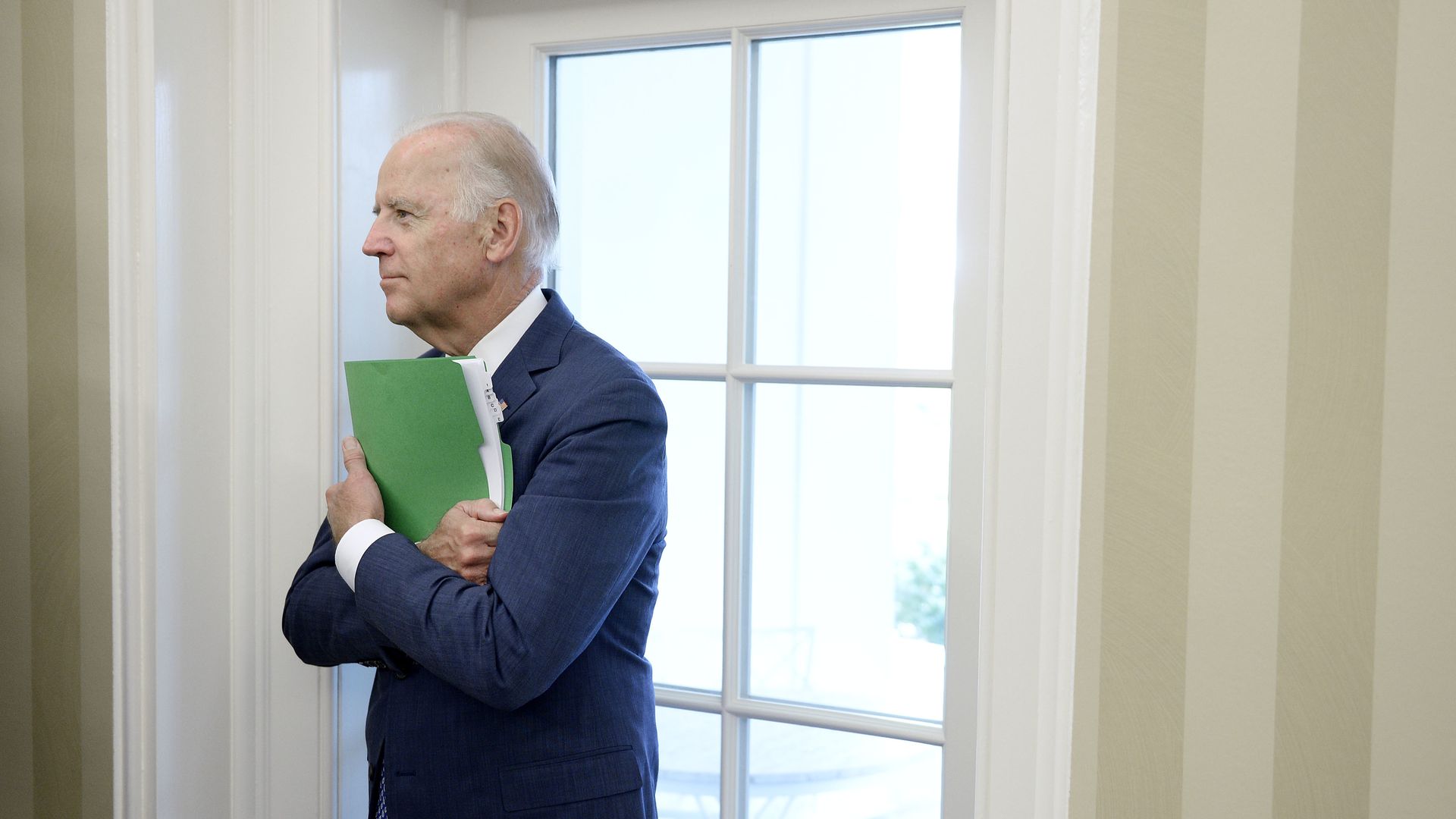

By Najia Houssari — arabnews.com — BEIRUT: A delegation from the American Task Force for Lebanon has stressed the importance of “establishing a social economic program before it is too late.” The call came after the delegation — accompanied by US ambassador to Lebanon Dorothy Shea — held talks with several Lebanese officials on Monday. Edward Gabriel, head of the ATFL, said: “Time is moving quickly, and the government must expedite laws and policies, carry out the required reforms, and take the necessary steps to meet the needs of citizens to push forward negotiations with the International Monetary Fund. We need a partner, and that partner is the government, which has to act quickly to achieve what is required from it.” The US provided aid worth more than $700 million to Lebanon last year, he added, and President Joe Biden “did not forget about Lebanon” during his Middle East visit.

FASTFACT MP Ibrahim Kanaan, chair of the finance and budget committee, announced the adoption of a law amending banking secrecy to prevent tax evasion, combat corruption, financing terrorism, and illicit enrichment. Biden mentioned several issues that affected Lebanon and stressed the integrity of the Lebanese territories during his meetings. The US call came as judicial assistants decided to join a strike of public sector employees on Monday, causing courts in Lebanon to grind to a halt. Public sector employees have been striking for about a month demanding that salaries be increased and for transportation allowances to be raised. The judicial assistants said they had stopped working permanently and would not make any exceptions, be they for urgent cases or public prosecutions, and would no longer issue notices on behalf of departments and courts.