by dw.com/ – In a bid to tackle water shortages, Lebanon is planning to build a dam close to two major seismic fault lines. Locals say environmental damage and the risk of earthquakes will outweigh the dam’s benefits. In a country notorious for its environmental scandals — including the two-year garbage crisis — the Bisri Valley, just 35 kilometers (22 miles) south of the capital, Beirut, feels like an Arcadian paradise. Its fertile soil nourishes a plentiful variety of fruit and vegetables, from olives and almonds to kiwis and pomegranates. It’s also famous for its pine nuts that grow wild on tall, umbrella-shaped trees (photo above). Adding to the valley’s charm, ruins that span several civilizations from the Phoenicians to the Romans are scattered along the Awali River. But all this is set to vanish. In an attempt to tackle ongoing water shortages, construction is due to start soon on Lebanon’s second biggest dam. The process is expected to take nine years and cost an estimated $617 million (around €518 million), funds mostly provided by the World Bank. The 70-meter (230-foot) dam on the Awali River will inundate 400 hectares (990 acres) of agricultural land, pine forests and natural vegetation. Advocates say the dam is essential to tackling water shortages that plague Beirut and its environs, home to 40 percent of the country’s population. Some neighborhoods only have three hours of water a day, according to the government’s Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR), which is overseeing the project.

Seismic disturbance But for the valley’s inhabitants the dam is a costly solution. Not only will they lose their farmland and livelihoods — they also fear the dam, to be built on an active seismic fault line, could put the region at risk of catastrophic earthquakes. Amer Machmouchi, a civil engineer who owns land in the Bisri Valley, is one of the dam’s fiercest opponents. He’s old enough to remember the devastating earthquake in 1956 that killed 135 people and destroyed his family home. “Any attempt to drill or dig in this area will allow water to run in the cracks,” he told DW. “Research suggests that extra water leakage into these cracks would lead to earthquakes, which would destroy all the villages. People will die in the thousands.” The Lebanon Eco Movement, a network of 60 local NGOs, also believes such a reservoir built on an active fault line could aggravate seismic activity. But Elie Moussalli, the engineer in charge of the project at CDR, insists their fears are unfounded. “The dam is designed to accommodate the maximum credible earthquake, which is equivalent to 8 on a Richter scale,” he said. “Studies were done according to best international practices.” But Machmouchi isn’t convinced.

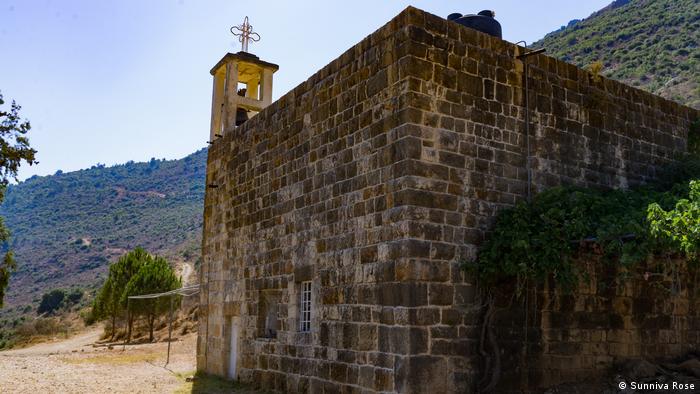

Flooding the breadbasket Among his favorite aspects of the valley are the Roman ruins that grace the verdant banks of the Awali River. The CDR has promised to excavate and relocate them, along with the historic Mar Moussa Church, at a cost of $370 million. Machmouchi remains dubious: “Who can move this temple? The area is 400 meters long. Where can it go?” Locals are also unhappy about the compensation the government is offering for the expropriation of their land. Marie-Dominique Farhat’s family owned 59 greenhouses that produce around 250 tons of strawberries a year. They have all been taken down to make way for the dam. “They will give us a compensation equivalent to only two or three years of harvest. Locals will become poorer,” she told DW. Farhat’s mother, 91-year-old Lody Awad, lives in an old house overlooking the valley. She said Lebanon, which has historically depended on agricultural produce imported from neighboring Syria, cannot afford to lose the Bisri’s fertile fields. “What is lacking here in Lebanon is agricultural land to feed the population, which is growing,” she told DW. “They need vegetables, fruits, of course, fruit trees, olive trees, and pine trees. If they take all this land — well it’s a pity, it’s a real pity.”

Authorities have promised to relocate the historic Mar Moussa Church, but locals are skeptical

Ecosystems under threat Roland Nassour, who prepared a report on the environmental risks of the dam on behalf of Lebanon Eco Movement, said wildlife is also at risk. The inundation will “obstruct movements of migratory water bird species,” as well as alter the river’s sediment levels and downstream flow patterns, he said. “It’s a whole ecosystem that will be severely impacted.” Environmental activists favor alternatives to the dam such as groundwater extraction. “We believe any water development strategy should consider investment in the underground water,” Nassour said. “About 65 percent of Lebanon’s water resources are actually in underground water basins.” Listen to audio 08:41 Living Planet: A high price for water? But a 2014 environmental impact assessment by the CDR says these were examined and discarded. The World Bank argues that Lebanon’s groundwater resources are already under pressure. “Currently in Lebanon, groundwater is overextracted by 200 million cubic meters per year and the aquifers are already being exploited at unsustainable levels,” a World Bank spokesperson told DW. Bisri’s last harvest? Despite opposition, construction of the Bisri dam looks set to go ahead. But that hasn’t stopped some landowners from continuing to tend to their orchards. Every Sunday, Oussama Saad still visits his fields of eggplants, prunes, almonds and nectarines, which his father purchased 60 years ago. “The connection between the land and the people is very strong,” he said, plucking a pomegranate from an overhanging branch. “I don’t want money. I want to live here. If we can’t stop the dam, I will see if I can find another piece of land. But I don’t think I can find a good place like this.”