By Ian Sample – theguardian.com

A huddle of seven worlds, all close in size to Earth, and perhaps warm

enough for water and the life it can sustain, has been spotted around a

small, faint star in the constellation of Aquarius The discovery, which has thrilled astronomers, has raised hopes that

the hunt for alien life beyond the solar system could start much sooner

than previously thought, with the next generation of telescopes that are

due to switch on in the next decade.

It is the first time that so many Earth-sized planets have been found

in orbit around the same star, an unexpected haul that suggests the

Milky Way may be teeming with worlds that, in size and firmness

underfoot at least, resemble our own rocky home. The planets closely circle a dwarf star named Trappist-1,

which at 39 light years away makes the system a prime candidate to

search for signs of life. Only marginally larger than Jupiter, the star

shines with a feeble light about 2,000 times fainter than our sun.

“The star is so small and cold that the seven planets are temperate,

which means that they could have some liquid water and maybe life, by

extension, on the surface,” said Michaël Gillon, an astrophysicist at

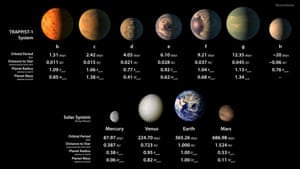

the University of Liège in Belgium. Details of the work are reported in Nature. While the planets have Earth-like dimensions, their sizes ranging

from 25% smaller to 10% larger, they could not be more different in

other features. Most striking is how compact the planet’s orbits are.

Mercury, the innermost planet in the solar system, is six times farther

from the sun than the outermost seventh planet is from Trappist-1.

Any

life that gained a foothold and the capacity to look up would have a

remarkable view from a Trappist-1 world. From the fifth planet,

considered the most habitable, the salmon-pink star would loom 10 times

larger than the sun in our sky. The other planets would soar overhead as

their orbits required, appearing up to twice the size of the moon as

seen from Earth. “It would be a beautiful show,” said Amaury Triaud at

the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge University

The researchers hope to know whether there is life on the planets

“within a decade,” Amaury added. “I think we’ve made a crucial step in

finding out if there’s life out there,” he said. “If life managed to

thrive and releases gases in a similar way as on Earth, we will know.”

Astronomers reported last year

what looked like three planets in orbit around Trappist-1, a star they

named after the Trappist robotic telescope in the Chilean desert that

first caught sight of the alien worlds. The telescope did not see the

planets directly, but recorded the shadows they cast as they crossed the

face of the star.

The discovery prompted more sustained observations from the ground

and space. Nasa’s Spitzer space telescope peered at the star for 21 days

and, with data from other observatories, revealed a total of seven

planets circling Trappist-1. The size of each planet was deduced from

the amount of starlight it blocked out, while the mass was estimated

from the way it was pushed and pulled around by other planets in the

system.

The planets are on such tight orbits that it takes between 1.5 and 20

days for them to whip around the star. At such proximity, most, if not

all, will be “tidally locked”, meaning they show only one face to

Trappist-1, just as one side of the moon always faces Earth. Some of the

planets are thought to be the right temperature to host oceans of

water, depending on the makeup of their atmospheres, but on others any

hospitable regions may be confined to the bands that separate the light

and dark sides of the planets.

Ignas Snellen, an astrophysicist at the Leiden Observatory in the

Netherlands who was not involved in the study, said the findings show

that Earth-like planets must be extremely common. “This is really

something new,” he said. “When they started this search several years

ago, I really thought it was a waste of time. I was very, very wrong.”

Astronomers are now focusing on whether the planets have atmospheres. If

they do, they could reveal the first hints of life on the surfaces

below. The Hubble telescope could detect methane and water in the alien

air, but both can be produced without life. More complex and convincing

molecular signatures might be spotted by Nasa’s James Webb Space Telescope, which is due to launch next year, and other instruments, such as the Giant Magellan Telescope,

a ground-based observatory due to switch on in 2023. But there is only

so much that can be done from afar. “We’ll never be 100% sure until we

go there,” said Gillon.

The conditions on planets so close to dwarf stars, which are known to

release fierce bursts of x-rays and ultraviolet light, might not be the

most conducive for life. But when the sun goes out in a few billion

years, Trappist-1 will still be an infant star. It burns hydrogen so

slowly that it will last another 10 trillion years, Snellen writes in an

accompanying Nature article. That is more than 700 times longer than

the universe has existed, so there is plenty of time yet for life to

evolve.

David Charbonneau, a professor of astronomy at Harvard University who

was not involved in the latest study, said a growing number of

astronomers were getting excited about what he called “the M-dwarf

opportunity” – the study of planets around such faint dwarf stars. “It’s

a fast track approach to looking for life beyond the solar system,” he

said.

M-dwarfs outnumber sun-like stars 12 to 1 in the Milky Way. In

previous work with Nasa’s Kepler planet-hunting telescope, Charbonneau

and his colleague Courtney Dressing, found that one in four of M-dwarfs

stars hosts a planet that is similar in size and temperature to Earth.

With the Trappist-1 observations, astronomers now know that Earth-like

planets circle nearby dwarf stars that can be studied with instruments

already in the pipeline. “This means we might be in the business of

looking for aliens in a decade, and not, as others have envisioned, on a

much longer timescale,” he said.