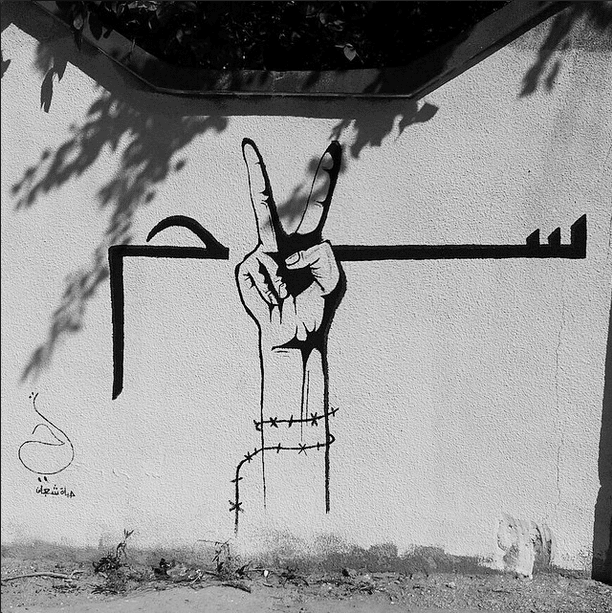

By Christine Petré wagingnonviolence.org . A black-and-white mural with the text “Salam,” peace in Arabic, with a hand wrapped in barbed wire making the peace sign, covers a wall in one of Tripoli’s more troubled areas. Its artist, Hayat Chaaban, who has lived in Lebanon’s second largest city her whole life wants to put art to the battered facades of Tripoli and defy the violence. By doing so she is not only challenging the city’s rough reputation, but also the perception that graffiti is a male-oriented activity.

In response to the “you stink” protests, Chaaban made this image of a garbage bag in the shape of Lebanon. (Hayat Chaaban)

Despite the risks, she isn’t afraid. Dressed in a hoodie and baggy jeans, she is one of the few female graffiti artists in Tripoli and most likely in all of Lebanon. The 19-year-old artist was also involved in the recent demonstrations against the government’s garbage management. In one of her pieces, she portrayed a garbage bag in the shape of Lebanon and underneath it she wrote “Enough!” The photo quickly became well-known and used by those in the movement. But her focus is Arabic calligraphy with social messages. “I don’t pick any side,” explained the street artist, “whether it be about politics or religion.” Chaaban’s work is instead about critical thinking and co-existence. But in a city like Tripoli, that is not always easy.

Tripoli has increasingly become known as a conflict-ridden place. Foreigners are advised against visiting and many Lebanese have never stepped foot in the northern coastal city. The reason behind the city’s violent reputation is closely related to a sectarian conflict between two neighborhoods, the Sunni quarter of Bab al-Tabbaneh and the Alawite area Jabel Mohsen. The old schism between the areas has intensified as a result of the continuing war in neighboring Syria. Most people in Bab al-Tabbaneh praise the uprising against President Bashar al-Assad, while the majority of the residents in Jabel Mohsen support the Syrian president. The city is also known as “Tripoli of Syria” due to its connection to the country’s war-torn neighbor. What happens in Syria is believed to have a direct effect on the Lebanese city. “It could even be argued that Tripoli has become an integral part of the Syrian conflict,” argued researcher and author Raphael Lefèvre in a recent report for the Carnegie Middle East Center.

In the area where Chaaban lives, Abu Samra, situated on a hilltop overlooking the city, hang posters of young men who died while fighting in Syria. Many are portrayed as martyrs for the Islamic State, which has a number of supporters in Tripoli. Several Islamic State affiliates have been arrested in the city. “They exist,” admitted Chaaban, “but it’s a very small group.” Yet, these individuals have contributed to Tripoli’s bad reputation.

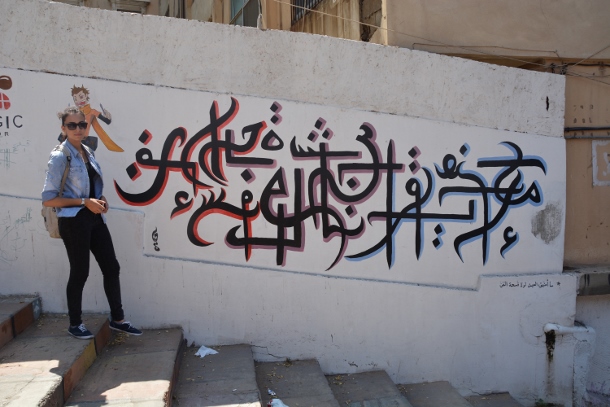

Hayat Chaaban stands next to one of her murals in Tripoli. (WNV/Christine Petré)

Strolling through downtown Tripoli, Chaaban shows her murals across the city center. The young artist points out that the city’s reputation is not representative of the city at large. It’s mostly isolated to certain areas and perpetuated by a small group of people. Chaaban hopes that her art will not only reinforce the city’s beauty, but also that its citizens will reflect on the murals’ social messages.

Nevertheless, a number of events have continued to taint the city’s reputation. In 2013, two mosques were targeted in an attack, which killed 47 people — making it the deadliest since the country’s 15-year-long civil war in the 1980s. Human Rights Watch called on the Lebanese authorities to protect Tripoli’s 500,000 inhabitants by confiscating weapons and arresting gunmen. “The Lebanese government can’t afford to sit on its hands,” stated the watchdog.

During one of the peaks of fighting in 2012 another of the city’s young women found her escape not in calligraphy, but in music. While the fighting escalated on a spring morning in May on the other side of the city, a piano tune would make peace advocate Heba Rachrach known. As she sat at home, the then-21-year-old started recording her song before she was disrupted by an explosion. But instead of stopping, Rachrach decided to stay resilient and continued to play, drowning out the noise with the sound of the piano. At the end of the day, she uploaded the clip “Stop the violence in Tripoli” on YouTube and it quickly went viral. “The bombings fulfilled people’s stereotypes about Tripoli because the city has a reputation of being unsafe,” explained Rachrach, “and home to terrorists and extremists.” Despite being safer than before, she argues, it is difficult for the city to break free from the negative connotations many have of it.

Heba Rachrach (WNV/Christine Petré)

But youth initiatives across the city are trying to change the city’s reputation. Rachrach is involved in perhaps the most well-known initiative, We Love Tripoli, which is trying to change not only people’s perception of the city, but also give voice to the youth through cultural and social activism by arranging events where they can come together and discuss their social grievances. Nobody is doing this type of work here, explained Rachrach. Perhaps that is why it has been so successful. Created in 2007 as a youth-led online community on Facebook, We Love Tripoli has almost 60,000 likes today.

“They do lots of social activities to make Tripoli a better place,” explained one of its supporters, 25-year-old Bassem Alameddine, who has been involved for two years. He was introduced to the initiative through a friend when he realized that many of his acquaintances were already involved. “I hope we can deliver a message to outsiders that the city is not as dangerous as they think,” he said. The city’s youth are keen to do social work to improve Tripoli, he explained.

We Love Tripoli helps young people to appreciate their city and thereby protect and care for it. The organization’s frequent activities include photography excursions, called “Shoot as you walk,” which aims to photograph new sides of the city and document its hidden beauty. This is Alameddine’s favorite activity, discovering his city’s gems. There are also regular movie screenings and workshops on topics such as recycling. The aim is to bring the youth together and promote a volunteer spirit to, for example, strengthen young people’s connection to their city and protect its cultural heritage. Many of the city’s young are keen to establish an alternative narrative to the mainstream about Tripoli. According to Rachrach the media is playing an essential role in presenting the city as conflict-ridden. However, there is more to Tripoli than the mainstream media headlines and its residents’ are working hard to prove it to the outside world.

—

This story was made possible by our members. Become one today.