The nail salon in the picturesque village of Ras Baalbek looks like any other nail salon in Lebanon. Located in the northeast of the country, close to the Syrian border, the predominantly Christian town is quiet today, drenched in June sunlight. A group of women chatter excitedly as they fan their freshly painted fingernails and examine their pedicures.

“You can’t see that color on your nails,” a pretty girl in her 20s says to her middle-aged, heavyset aunt, who is drying her toes. “You should have picked a different color.”

Her mother laughs. “Look at us, there’s a war and we’re doing our nails. And next week there will be a wedding in the village. We must be very confident.”

Her aunt snorts. “Well, all I can say is, I’ll kill myself before I let them take me.”

The girl tuts at her. “Hush, tante. Hezbollah won’t let that happen.”

“Well, if Hezbollah leaves, I’ll pick up my ass and follow them,” her aunt says, to much hilarity. It’s clear she’s accustomed to provoking shocked laughter. “Because God help the Lebanese army, they couldn’t stop daesh alone … If Hezbollah wasn’t here to protect us, daesh would have fucked all our lives.

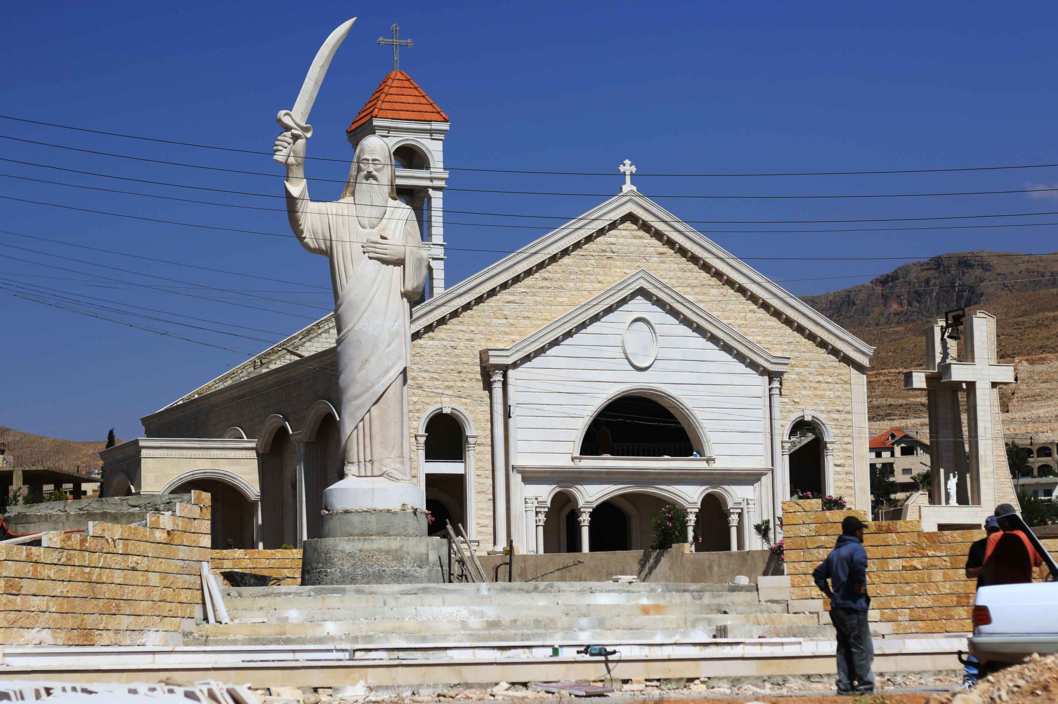

The truth is, this nail salon is doing business in a very dangerous place. Ras Baalbek is right on the border between what is still Lebanon — a multi-sect country used to a relatively liberal, relaxed lifestyle — and the fundamentalist, violent rule of the Islamic State’s “Caliphate.” Beginning in August 2014, ISIS, which is commonly referred to in Lebanon by the derogatory name daesh, and its frenemy Islamist group Jabhat al-Nusra separately mounted a series of incursions across the Syrian border into Lebanon. In fact, there are just two small, sparse, overlapping mountains — more like hills, really — standing between Ras Baalbek and the neighboring town of Arsal, parts of which are now in ISIS and Nusra hands. The militant groups hold the outskirts, some of the nearby hills, and have a heavy underground presence in town.

Media reports from the area are rare, given ISIS’s habit of kidnapping and beheading journalists, but to give an idea of what’s at stake for these women, ISIS is already reported to have established an Islamic Shariah court in Arsal. Were the militants to be successful in taking the Christian village, the days of short-sleeved shirts and uncovered hair would be over. Not only that, but as a minority despised by the radical Sunni Muslim groups as infidels, they would likely be exposed to the hell of forced marriage and systematic rape that other women of minorities have fallen victim to when ISIS captures their land.

Make no mistake, ISIS has designs on Ras Baalbek. The group has a preoccupation with expanding their Caliphate over much of the Middle East, and as a fragmented state plagued by old sectarian hatreds, Lebanon is a natural place for them to attack. So far, their efforts have been modestly rewarded: They now control approximately 130 square miles of Lebanese territory. As a result, the Lebanese army and its longtime rival Hezbollah, the powerful Iranian-backed Shia Muslim militia, have found themselves battling ISIS alongside each other, if not necessarily together. Apart from Lebanon’s radical Sunni Muslim population, which is largely concentrated in the northern town of Tripoli, all four of the country’s major sects (Sunni, Shia, Druze, and Christian) are having the unusual experience of standing united in at least the desire to prevent ISIS from gaining a foothold in Lebanon.

The combined forces of the Lebanese military and Hezbollah, as well as ISIS’s preoccupation with its efforts in Syria and Iraq, make it unlikely the group will be able to easily take much more territory here. Still, there have been worried whispers about ISIS sleeper cells planning to commit acts of terrorism within Lebanon. And always in the background, there is the possibility of a large-scale sectarian conflict, which has haunted Lebanon since the end of the civil war and is now a very real threat with spillover from Syria.

Aram Nerguizian, senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, D.C.–based think tank, explains why the militants are so focused on the area. “Ras Baalbek ties into a road network," he says. "The challenge that faces groups like Jabhat al-Nusra or ISIS is that they’re operating in a region that is very, very arid. Road networks mean resupplies, access to water and fuel.”

Until earlier this month, ISIS had only been attacking the Lebanese Armed Forces stationed near Arsal, while Nusra confronted Hezbollah, which has been battling them elsewhere in the area and within Syria, in support of the Assad regime. (The relationship between Nusra and ISIS is complex, and although there has been limited cooperation between the religiously like-minded groups on the Lebanese front, they routinely fight each other in Syria.) But on June 9, ISIS launched an attack on Hezbollah positions just outside of Ras Baalbek, attempting to gain control of the hills between the villages, and likely aimed to capture Ras Baalbek as well. The number of casualties from this fight are contested, as most war casualties are: Hezbollah claims it killed hundreds of ISIS fighters, while other reports number the dead anywhere from 22 to 80. Either way, Hezbollah triumphed, winning the hearts and minds of Christian villagers, including the ladies in the nail salon. It has continued to mount a successful offensive against ISIS since, reportedly killing the group’s local “emir” last week.

But Hezbollah also lost fighters in the June 9 attack, and one of their unit chiefs, a tall, lean man we’ll call Abdullah, says that’s because although Hezbollah was aware there would likely be an attack on their positions, they were taken by surprise that day.

“We were prepared for them to come eventually, but since we were already fighting with Nusra, our plan was to spread the battles out,” says Abdullah. “But daesh made that impossible, and now the war has started. When they came at us, we gathered our forces, and because we were prepared, they had very high casualties. But we lost nine of our fighters, and it’s too bad, because we wouldn’t have lost anyone if we were ready for this attack.”

Asked why Hezbollah took such pains to protect a Christian town, Abdullah shrugs. “Christians have a holy book just like us,” he replies. “They’re people just like us. They’re Lebanese, so we protect them.”

It’s a role most Americans wouldn’t associate with Hezbollah, which remains on the U.S. State Department’s terrorism list as a result of bombings and kidnappings of U.S. citizens associated with it during the Lebanese Civil War. But to the people of Ras Baalbek, Hezbollah is their only hope of holding on to the life and village they’ve always known. A man who owns a small grocery store in the middle of town says he did what he could to assist Hezbollah as they battled ISIS in the hills outside the village.

“If it weren’t for Hezbollah, you would be seeing daesh playing in our village right now,” he explains as he pours a glass of lemonade. “We’ve never seen anything bad from Hezbollah — the army can’t defend this whole area. If daesh comes, God forbid, we know what will happen to us. We saw what they did to the Christians in Syria and Iraq. That’s why we’re on alert, thanks be to God and to Hezbollah, who are protecting us. I have an injury from the war, so I can’t walk very well, but I helped them fill their guns with bullets.”

Two ancient men basking in the June sun across the street appear to be the town’s other watchful guardians. One of them laughs when asked if they’re afraid, his wrinkled face breaking into a wide, yellow-toothed grin.

“The situation is fine,” he chuckles in his cracked voice. “We are very calm.”

He points to the small mountains separating them from ISIS. “Daesh tried to make a push from right there. They thought they could easily take the town because it’s small, but they didn’t know the people of this town were ready to fight alongside Hezbollah in the mountains.”

There are plenty of people in Lebanon who chafe at the portrayal of Hezbollah as selfless heroes defending their country. A prominent Lebanese politician who prefers to remain anonymous says the group is primarily concerned with protecting its supply lines, not saving Christians from ISIS. Because Hezbollah is fighting in Syria with the Assad regime, they need to maintain the flow of goods and weapons necessary to sustain their troops. “They feel the threat of Syrian rebels and for them it is a very crucial area."

According to Nerguizian of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the Lebanese army’s successes in the area are being overlooked, while Hezbollah is enjoying all the glory. “Hezbollah has been stealing the headlines because they’re very good at it,” he says. “They’re very good at saying, ‘We’re the ones defending Christians, we’re the ones defending the country.’ What isn’t going to be talked about is the massive scale of artillery fire by the Lebanese military, independent of what Hezbollah is doing.’”

Retired Lebanese army chief Ibrahim Tannous says he views Hezbollah as a threat to the sovereignty of the army and the state, because they act as agents of Iran, not Lebanon. “For the moment, they need the LAF," he says. "But what’s going to happen after the war is finished? That’s the problem.”

This is a long-term worry, though. For the moment, Hezbollah fighters and Lebanese army soldiers alike are thinking about the battle at hand. Abdullah, the Hezbollah unit chief, explains his greatest fear — that Nusra and ISIS will mount a large-scale offensive against the Lebanese army in the northeast while multiple ISIS sleeper cells across Lebanon simultaneously activate and carry out massive acts of terrorism.

“If you want to ask me personally, we should fight the daesh supporters here in Lebanon,” says Abdullah grimly. “I feel a sectarian war is coming. We know there are people with daesh forming sleeper cells within Lebanon. We have to study the whole situation, the whole region, and then we’ll know which move to make. We are the only thing protecting Lebanon from those animals.”

There’s no question it’s a dangerous time to be living on the border. But the people of Ras Baalbek, so precariously perched on the line between the Lebanon they understand and the Caliphate they fear, say they won’t run if the men haunting their nightmares come back. The man in the grocery store is determined as he sips his lemonade.

“My father was born here, my grandfather was born here, my uncles, all my family was born and raised in this village,” he says. “Would it make sense for me to leave it now? I’ll die here, no matter what.”

In the nail salon, the women continue their debate over whether they should be afraid. The girl’s mother shivers dramatically.

“We are afraid of the way they look,” she says. “Their faces frighten us.”

The girl nods. “As Christians, we’re in a lot of danger, because we’re like a small island in a sea of Muslims,” she explains. “We are friends with Muslims; we don’t hate them. But these aren’t Muslims, they are terrorists.”

A lady who has remained quiet as her fellow clients argue suddenly speaks up.

“If you want to know whether the women of this village will run away, we will not,” she says fiercely. “I’m a grandmother now, I have three grandchildren, and I’ll pick up a weapon myself and kill them.”