Within the confines of Lebanon’s Roumieh prison they gathered

together as men recounting lives led before they became seen as

terrorists. Inmates whose affiliations spanned across Islamic State (IS) and a

gamut of other Islamist groups were in discussion and, for once,

religion and politics were not on the agenda.

Instead, led by two pioneering social workers, the talk was to be of their fears, their hopes, their regrets. “The moment you refer to religion or politics it becomes an endless

debate,” explained Nancy Yamout, who along with her sister Maya has been

overseeing sessions that also include art therapy.

“Religion is part of it, of course, but we’re not sheikhs, we’re social

workers. We want to look at how they have reached this point socially

and psychologically.”

For five years they have worked within the prison as they search for a

new way to respond to radicalism, a search that is now taking them from

the Islamists of Roumieh prison into neighborhoods of the dispossessed.

Beyond the sectarian

A country deeply divided along sectarian lines, Lebanon’s instability has increased with the Syrian war.

Struggling with an influx of Syrian refugees, the country also finds

itself under threat of bombing – the last deadly blast took place this

June in the northern border town of al-Qaa and state security services

claim to have foiled numerous other IS attacks.

This neighborhood in west Beirut is the target of the Yamout’s efforts to prevent radicalization.

Meanwhile some youngsters within Lebanon’s own borders are being lured by the likes of IS into the conflict.

Some of the main drivers behind this are well established.

Raphaël Lefevre, a fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut,

told VOA that recruits were “young Sunnis who feel strongly about

supporting the Syrian revolution.”

Referring to the role of the powerful Iran-backed Lebanese Shia group

which intervened to support Syrian Prime Minister Bashar al-Assad, he

explained they “also feel frustrated by Hezbollah’s intervention in the

ongoing conflict there and domination in Lebanon.”

The same year the war began, 2011, the Yamout sisters entered Roumieh prison for the first time.

A bar of soap, one of many items the Yamout sisters bring in to Roumieh prison for the inmates.

They had both lost friends to radicalization, and persuaded the

authorities to let them in as they sought to understand what it was that

drove people into the arms of islamist militants.

But, as social workers, they wanted to look beyond the religious and political context of their subjects.

Building trust

Nancy and Maya Yamout have slowly built trust among inmates in Roumieh’s

Block B, exclusively home to the prison’s 680 Islamist militants, as

they go about conducting interviews rather than the more usual

interrogations.

“We don’t ask them why they are accused of terrorism,” explained Nancy.

“We ask them how they are doing, what are their happy memories, what kind of food do you like?”

The latest art sessions were created as a form of therapy, though the

sisters had limited material at their disposal — the prison would not

allow chalk because it could potentially be smeared by inmates across

the prison’s CCTV camera lenses.

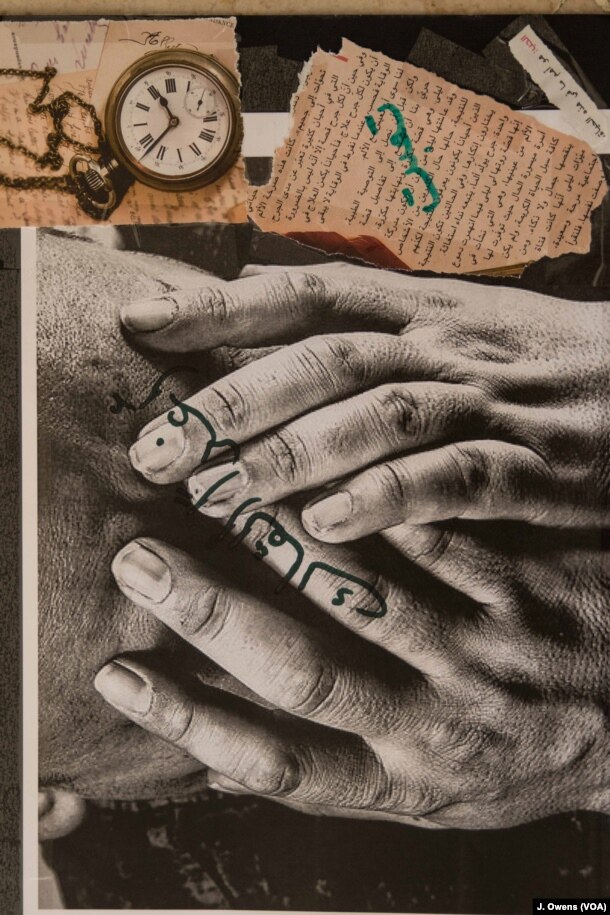

One of the artworks created by an inmate in Roumieh

Prison after art therapy. Some refused to draw or paint, considering it

against Islam, but used photos instead. The words “I’m tired” and

“tomorrow we will meet” are drawn over the work.

Such workshops act as a gentle entry into discussions exploring the

circumstance that created men seen as monsters by much of the outside

world.

The Yamout’s findings led them to explore the role of family, and the support mechanisms available.

“If they’re between 15 and 20, they are developing their ideology, and

if the parents are not creating a sense of self worth, or even something

like the Scouts or Red Cross is, others will,” explained Nancy.

“It’s about a sense of belonging, of being wanted,” added her sister Maya.

And now, armed with their findings, they have moved beyond Roumieh in an effort to stop the cycle before it destroys more lives.

Reaching out

Having come to Lebanon from Manbij, the Syrian town controlled by

Islamic State until August, Amal* has left one nightmare to be

confronted with another.

Living in a poverty-blighted neighborhood in west Beirut, she fears for

the safety of her children in a place she says is rife with crime.

“Maybe children here will reach drug dealers, or extremists – I don’t know,” she told VOA.

The Yamouts were pointed in the direction of the neighborhood by their contacts within Roumieh.

Here, claim the sisters, is a toxic mixture that contributes to

radicalization – poverty, but more importantly broken social structures

and familial relations.

Many here also lack Lebanese citizenship, making them vulnerable,

according to the sisters, to those offering a new sense of identity and

purpose.

In response, the Yamouts and their NGO Rescue Me have set up workshops

for youngsters, offering them therapeutic activities like mosaic-making

and job training, and are also setting up an office in the neighborhood

to offer more permanent support.

Nancy, Maya and their mother at their home, from which they run their NGO Rescue Me.

Oil on fire

“When you support these kids, and give them enough, their self esteem rises and they gain the tools to work,” said Maya.

The sisters are tireless in their work, but the challenge they face is daunting, while their funding remains threadbare.

Advocating for more focus on prevention of radicalism at its roots, with

supporting families in vulnerable communities crucial, they argue that

more effort needs to be made helping former prisoners leaving Roumieh’s

Block B into Lebanese society.

Otherwise, they warn, no matter how many arrests are made, or how many

end up in Block B, the cycle of violence and radicalization could

continue.

“The message [of Islamist militants] can spread,” warned Nancy. “It’s like oil on fire.”

*Amal’s name has been changed to protect her identity.