Lebanon is just over half the size of Leinster, but by virtue of its proximity to neighbouring Syria, it has borne the brunt of the number of refugees fleeing across the border to escape civil war, writes RTÉ’s Aengus Cox.

At the beginning of December 2015 there were an estimated 1.2m displaced Syrians spread across Lebanon, comprising more than a quarter of the country’s population.

With the high number of refugees, traditional camps have not proven sufficient to cope with the escalating crisis.

In Lebanon there is now an established profile of both rural and urban refugees.

The capital Beirut, for example, is now home to at least 50,000 Syrians who have fled their homeland.

They are not living in the tents that many would usually associate with refugee accommodation, rather they are living in what were originally urban camps populated by Palestinians.

Many of these camps in Beirut have been in operation for more than 60 years, and have evolved over the years into sophisticated slums.

The Palestinian residents here, who in many cases include two or three generations of the same family, have welcomed the Syrians with open arms, and the two cultures live side-by-side.

Conditions here though are far from ideal, with cramped living spaces littered with bullet holes, rolling blackouts, little or no sanitation, and very little food for the 50,000 inhabitants.

Makeshift overhead electricity and water supply cables hover dangerously close to the ground.

With food scarce, the Dublin-based charity Human Appeal Ireland (HAI) has set up bread distribution centres in some of the camps, however, with rising numbers the schedule has had to be revamped.

HAI Manager Belkacem Belfedhal says that as a result of the increased number of people in need of its bread, the charity has had to allocate specific days to families for deliveries.

One day the Syrian families will get bread, with Palestinians the following day. There simply isn’t enough to go around for an adequate daily supply, and that’s the harsh reality of the swelling numbers.

The Syrians in this Palestinian camp are nervous, reserved and reluctant to interact with strangers.

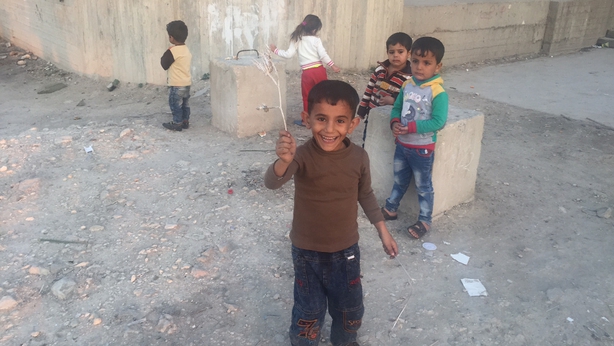

However, 40km south of Beirut in the city of Saïda, hundreds of Syrian families have taken up residence in an abandoned semi-constructed building that was once destined to be a university.

The refugees here are much more willing to interact with visitors, especially the children.

This is likely down to the fact that they are only here a short time, and do not have much experience of the daily hardship that comes with being a refugee in the region.

Again, living space here is at a premium, with generations of the same family, often numbering well into the teens, cramming into one or two small rooms, while basic requirements such as sanitation and electricity are a luxury for the lucky few.

The urban refugees in Lebanon make up just one small part of the narrative, as to the east in rural camps in mountainous regions along the Syrian border the elements really come into play.

At night in December and January temperatures fall well below 0 degrees Celsius, and with people here living in tents there is little protection from the freezing conditions.

One resident, a man who fled across the border from Homs, has been living in a camp here near the town of Arsal for nearly three years.

He explains that last year it was so cold for a three-week period that many of the women and children in the camp travelled to the mosque in the local town to sleep at night.

Otherwise, he said, they would surely have died. He backs up his point by telling me a story of how some mornings during the harshest of conditions it would not be uncommon to find the bodies of men, women, and children who had succumbed to the elements during the night.

Human Appeal Ireland is one of the few agencies currently distributing bread, food parcels, and fuel to refugees in the area.

Volunteer with the organisation Fiona Duffy explains the importance of the fuel that the charity distributes as often as it can to camps in this part of the Bekaa Valley.

“Fuel is used for heating, cooking, and staying alive basically,” she stresses.

She adds that refugee numbers around the town of Arsal have swelled, with the population now over 150,000 – three times higher than it had been prior to the breakout of the Syrian civil war.

As a result, supplies need to be stretched and last longer, meaning the fuel delivered on the day we were visiting the camps in the region would only last families for around four days.

Education still on the agenda

As the number of Syrians fleeing civil war increases by the day, the demand for essential aid becomes even stronger – with the result that concerns such as education have fallen down the pecking order.

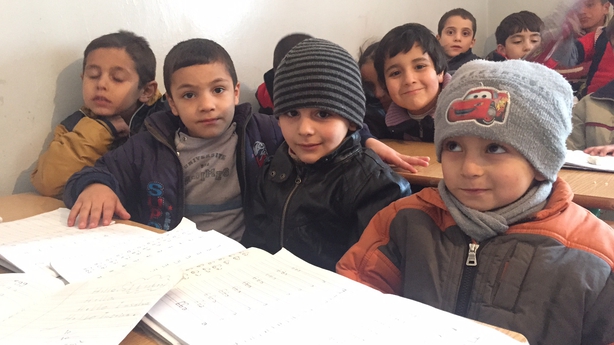

However, high in the hills above the refugee camps in Arsal in the Bekaa Valley there are efforts under way to keep refugee children in school.

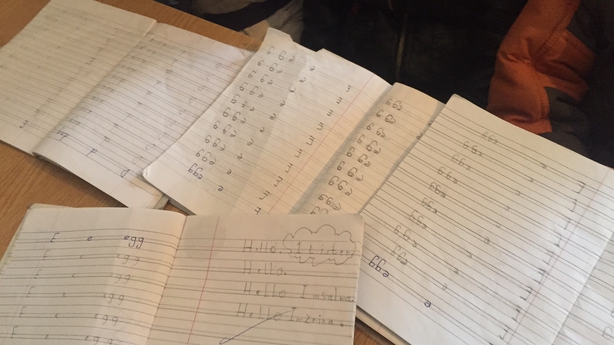

A local property owner here donated one of his buildings to be used as a school, where there are around 500 Syrian pupils. But resources are scarce and all the teachers volunteer their services.

Shortly before Christmas the school was near breaking point, with volunteers unable to continue to offer their services without pay, and donations drying up.

But, thankfully Human Appeal has stepped in and, with the school in immediate danger of closure, has managed to secure funding to keep it open into 2016.

The administrators are also seeking funding from local government in eastern Lebanon to ensure the long-term future of the school.

With people struggling to keep warm and maintain an adequate and regular food source, causes such as education can be challenging to secure support for.

The teachers in this school though, many of whom are Syrian refugees themselves, seem resolute to fight for education, and from a trip around the classrooms and short interactions with the children the importance of education is obvious.

It keeps everyone engaged, and offers a sense of normality that otherwise would be non-existent living in a makeshift tent on a mountain in a strange country.

Importantly, projects such as the school also offer some hope, which is crucial given that the refugees living in the region will likely be here for a lot longer than anyone had planned.

http://www.rte.ie/news/2016/0101/757315-spoe/