![]()

By Huffington Post-

Do Middle

East/North Africa (MENA) consumers and producers of media in all their

permutations and across countless platforms fully comprehend what

they’re doing and how they fit in the larger scheme of things?

Do various

groups and individuals take the time to deconstruct messages, processes,

outcomes and repercussions of all the interactivity, integration,

convergence and overwhelming flow of communications that keeps morphing

into new shapes at speeds we can hardly keep up with?

It’s as dizzying

as Mork from the planet Ork, American comedian Robin Williams’ famous

TV character, credited in part with paving the way to our truncated

media consumption habits from back in the 1970s.

“Robin Williams Was An Unwitting Prophet of the Internet Era,” headlined Business Insider to a story about Williams’ frenetic and breathtaking influence on us.

According to

writer Aaron Gell, Williams channeled culture; his cut-and-paste style

echoed what rappers were doing with samples, and like them, he

occasionally got into trouble for borrowing material.

“It’s only now,

in retrospect — in the era of broadband and ‘an app for that,’ Twitter

and subreddits, and binge-watching and channel-surfing and emojis and

Google Now and instant everything everywhere at all times — that we can

really see where he was coming from, acknowledge the debt we owe him and

spot the warning flares he was sending up,” Gell said.

When news went viral of Williams’ suicide in August 2014, media and citizen journalists worldwide were all over the map reporting it – many in very poor taste.

A day later Lebanon’s Future TV‘s

website upped the ante by showing a photo purportedly of Williams’

corpse with the mark of the belt he used to hang himself around his

neck, which several websites later said was a fake.

Such sights and

earlier violations got me interested in the 1990s in media ethics (or

the lack thereof), explaining the media’s role and power, demonstrating

how to use media to create better engaged and more tolerant citizens, as

well as developing awareness about the need for media and information

literacy on all fronts.

While serving

as coordinator of the journalism program, director of university

publications and eventually director of the Institute for Professional

Journalists (wearing three hats) at the Lebanese American University, I

participated in 1999 in a virtual cross-cultural academic and

journalistic experiment with Professor Roger Gafke and his students from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism.

It was a

rich exercise in cross-cultural communication, values, newsworthiness,

the use of nascent technology (notably the Internet in Lebanon) and

finding out what really mattered in a media environment to people on two

different continents.

Fast forward to

2002 when I examined how Lebanese and Middle East media covered the

September 11, 2001 attacks on the U.S. in an article for the (defunct)

Lebanon Journalism Review’s Spring 2002 issue entitled “Keep Kids in Mind When Writing that Story: Are Detailed Graphics Really Worth It?”

Reactions

were varied, but often based on their (children’s) own experiences with

violent TV shows, epic Hollywood movies, or, science-fiction video or

computer games. But when the reality began to sink in, thanks to the

endless replay of the horrific footage, fear and incredulity also took

hold.

In May 2004, I presented a paper entitled “Media Literacy: Awareness vs. Ignorance” at the seminar “Young People & the Media” organized by the Swedish Institute in Alexandria, Egypt.

In it, I asked

if children knew what they received as information, if they evaluated

content, if their parents and teachers were helpful in selecting

programming, or if they let young people judge for themselves what was

suitable for reading, listening, watching or browsing.

Subliminal

messages tucked into programs may influence purchasing patterns.

Conflict-filled episodes or video games could incite violence and lead

to aggressive behavior. Even innocuous-seeming serials could traumatize

young people into confusing fantasy with reality. All with the end

result that an unsophisticated approach to the consumption of news,

entertainment, and even the more popular “edutainment” may contribute to

dysfunctional societies and individuals, or, at the very least,

confusion about how to react to the cacophony of messages overloading

our sensory circuits.

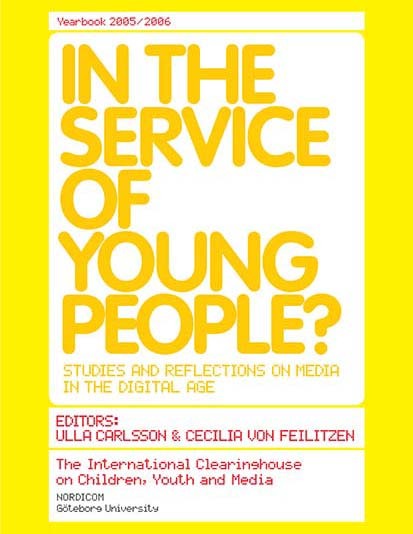

In November

2004, I delivered a lecture entitled “Lebanese Youth & the Media:

Social & Political Influences” at the “German-Arab Media Dialogue”

at a conference organized by the German Foreign Ministry and Institute

for Foreign and Cultural Affairs in Berlin.

Nordicom Clearinghouse in Sweden published it as a chapter in the book “In The Service of Young People?” in September 2005.

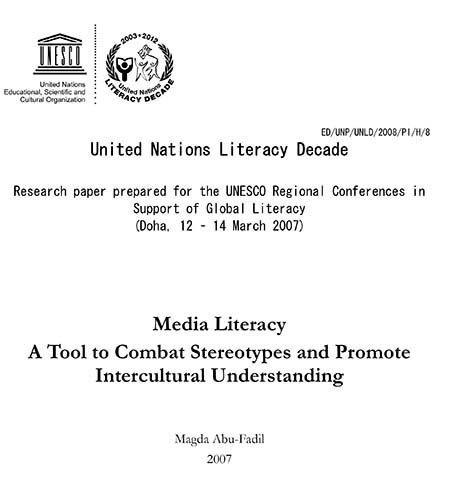

In March 2007, I

presented a research paper for the UNESCO Regional Conference in

Support of Global Literacy in Doha, Qatar entitled “Media Literacy: A Tool to Combat Stereotypes and Promote Intercultural Understanding.”

The very

concept of critical thinking that underpins media literacy seems alien

to young people weaned on a steady diet of rote learning and passive

intake. This is particularly evident in schools following the French and

Arabic educational systems where the very idea of questioning authority

has, traditionally, been anathema. Even British and American systems

have sometimes fallen short of their stated goals of effective learning

and questioning.

In January 2008, I presented a paper at a UNESCO conference on cultural diversity and education.

A major report grew from the initial event in Barcelona, Spain and was launched at the UN’s Alliance of Civilizations in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in May 2010 where my recommendations from the first conference’s paper were included.

Since then,

I’ve lectured on the topic and conducted workshops on media and

information literacy in Lebanon, Qatar, Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen.

So how do we contribute to media and information literacy in Lebanon?

Gaming is one way to channel young people’s energy and is a booming industry that caters to multiple tastes.

Games,

particularly the electronic and virtual varieties, are used in education

to teach life skills, mathematics, science, languages and a host of

topics, both as standalone software and as applications.

But games and “apps” also come in sinister forms with a heavy emphasis on violence, wars, and deviant behavior.

With wars

raging in various Arab countries and instability ruling the day in

Lebanon, it’s important to demonstrate to impressionable young people

that games based on conflicts are not necessarily good examples to

follow.

Animated

cartoons, another form dear to young and old, can be instrumental in

promoting and perpetuating stereotypes, reflecting positive and negative

images, and in prompting actions and reactions. The trick is to

capitalize on the positive.

Their

predecessors, comic books, have also had a similar effect on readers who

sometimes mixed myth with reality. They are still a popular form of

media and can be used to good effect in teaching and learning.

In Lebanon,

comic books are available mostly in Arabic, French and English, although

these publications can also be found in other languages.

Newspapers and

magazines are not as dominant as digital and mobile media and radio

plays a secondary role to online audio and video content.

Television was

once termed a “babysitter” when parents sought to pacify their children.

It has since taken a back seat to all things mobile and online and in

which user-generated content is ubiquitous.

Implementation

of programs that promote digital knowledge along with media literacy is

where the heavy work is needed and given the country’s geographic

location, there’s an urgent requirement to provide more practical

content in Arabic, while producing materials in French and English to

cater to the different sub-groups.

(This is a summary of a chapter by the author, also the lead editor, in the just published English/Arabic book Opportunities for Media and Information Literacy in the Middle East and North Africa,

published by the International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth &

Media at Nordicom, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, with support from

UNESCO and the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations)