By Jenny Gustafsson in Beirut – The guardian — ‘Reformists’ take on the corrupt ‘elite’ in a game that recreates the golden age – and invites players to imagine a different history

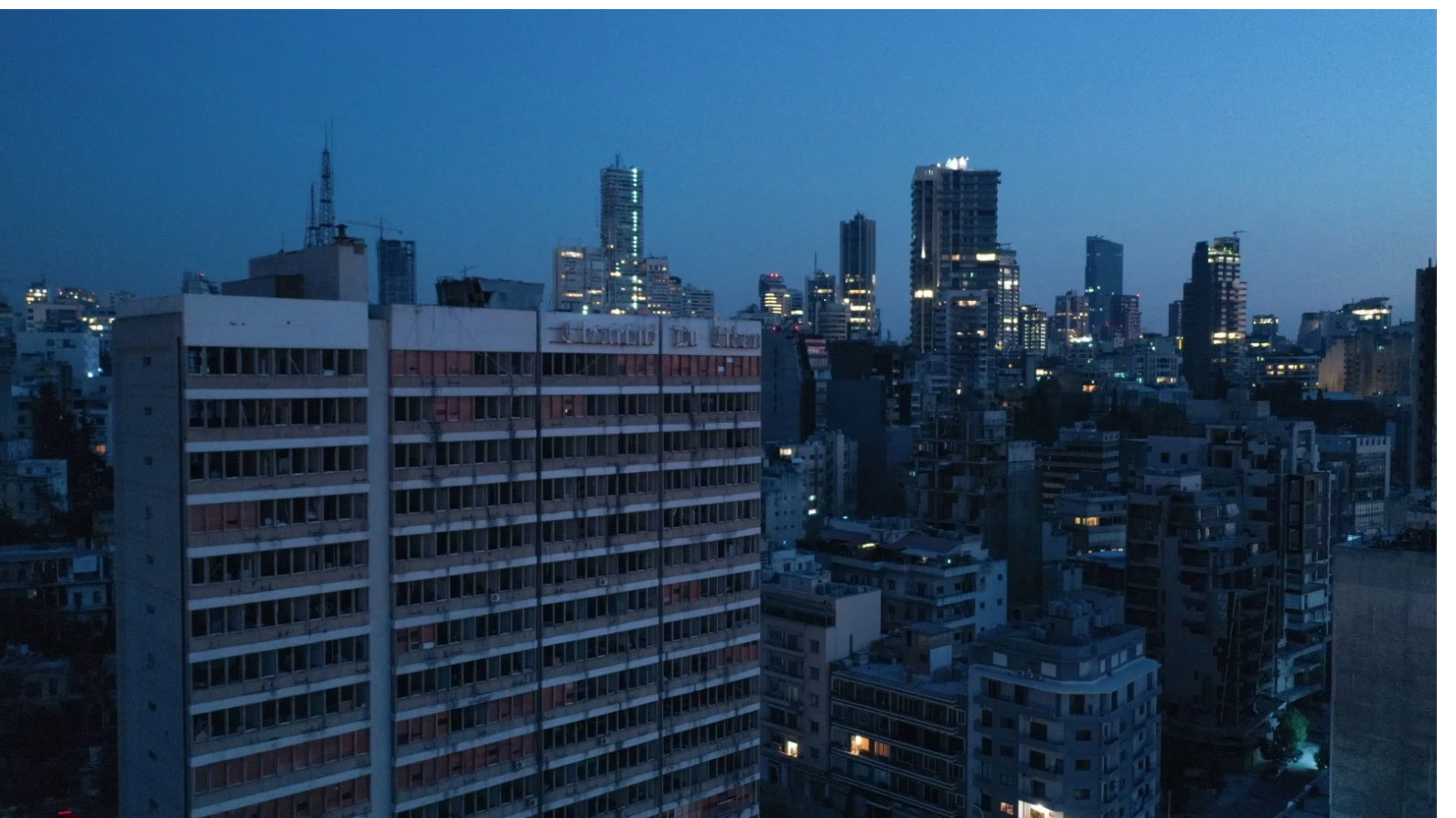

In a dimly lit room in Beirut, five friends sit around a table with a map of Lebanon in the middle. They each have a handful of markers and a card placed face-down in front of them.

The card, which has a drawing of a vintage chair on the back – symbolising power – determines the entire game. It assigns you the secret role of either “reformist” or “corrupt elite”. “It is just like in real life, you don’t know who is corrupt and who is not,” says Jean-Michel Chemaly, one of the developers of the board game. Machrou3 Ra2is: A Game of Corruption was released in December, giving people a chance to play the political game of Lebanon. The task is to control districts and, ultimately, win the presidential election – either through bluff or fair play.<p>

Chemaly says the idea came during the protests in 2019, when large numbers of Lebanese came out on the streets. A friend, Benoit Khayat, suggested that they create a game based on the politicians’ actions. “Every single society has people abusing power for their own benefit. We wanted to speak about it from a Lebanese perspective,” Chemaly says. The issues that people mobilised around in 2019 – corruption, accountability, justice – have become even more pressing. Lebanon has sunk deep into a financial crisis, with one of the highest levels of inflation in the world and a 98% depreciation of its currency. A fledgling anti-corruption movement has lost momentum. Millions have lost money, and are unable to access what little is left due to bank limits on withdrawals. As a consequence, 80% of the population face poverty, the UN estimates.

Politically, the country is in a vacuum. In last year’s elections more reform-minded candidates than ever before ran for seats, and parties affiliated with the protest movement got 13% of the popular vote. But the country has been without a president since. In addition, no one has been charged for the huge explosion in the port of Beirut in August 2020, which killed more than 200 people. “We have absolutely no say in the politics of the country. Creating the game was a way of bringing about some agency,” says Rana Zaher, the game’s illustrator. Her aim was to make the game look like “something you would find in your grandma’s closet”. The map has a vintage feel, with stains and smudges. The characters from camp “reform” and camp “corrupt” all wear styles from the 1950s. One smokes a slim cigarette, another holds up a camera with a handheld flash. A man with a fez on his head poses with a “I won’t name any names but the characters are modelled after real political figures,” Zaher says.

All the reformists are drawn in dark red, the corrupt characters in green. “Green symbolises sickness and death, and isthe colour of money, of course,” she says. The idea was to set the game in Lebanon’s golden age, and pose the question of whether circumstances then were setting the scene for the crisis today. “We wanted to know how we got to where we are today. You have to go back 100 years to find out what went wrong,” Chemaly says. It is not the first board game to look for new ways to explore politics and history.

In 2019, Indian developers launched Shasn, Sanskrit for “governance”, where questions about ethics determine whether you’re an “idealist”, a “capitalist” or a “showman”. An updated version of the 2002 game Puerto Rico, which originally had players in the role of colonial governors, was released last year. The original game had faced criticism for its portrayal of colonialism, failing to include the experiences of people who lived through it. The new version is set in post-independence Puerto Rico. That game led to the creation of the “counter-colonialist” game Promesa, where players can learn about the Puerto Rico’s debt crisis. It is named after the 2016 law that handed control of the island’s finances to the US. Machrou3 Ra2is is on sale in shops throughout Lebanon and online, and has sold 500 copies so far. At a comic convention in Abu Dhabi in March, the team sold the game to visitors from Qatar, Australia and the Philippines.

Chemaly says the game, which is in English, can be played by people anywhere to help people see what real life corruption looks like. “It depicts the struggle of every country in the world, people trying to make sure that the good guys get to power,” he says. Around the table, the game is drawing to a close. The final vote for president turns into an extended debate with everyone trying to call each other’s bluff– proof that it has been a good round, Chemaly says. “When it ends with a 30-minute discussion, you know you had a good game.”