france24.com

Every summer, thousands of Gulf Arab tourists — some with maids and staff in tow — descend on Lebanon, triggering quintessentially Lebanese jibes about the annual wave of moneyed “khalijis,” or Gulf natives, arriving on their shores mixed with an acknowledgment of the much-needed tourist revenues they generate.

Barring an outbreak of war, khalijis can be unfailingly spotted in the holiday season in Lebanese hotels, restaurants, and the infamous seaside resort of Maameltein — famed for its sleazy “super nightclubs” – where Gulf tourists let their hair down and do their bit for the tiny Mediterranean nation’s coffers.

This time though, the summer migration could dwindle to a trickle as tourism becomes the latest victim of the complicated relations between Sunni powerhouse Saudi Arabia and Hezbollah-dominated Lebanon.

Last week, the Saudis and a number of Gulf States urged their citizens not to travel to Lebanon. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) went a step further by banning their citizens from travelling to Lebanon and reducing its diplomatic missions in the country.

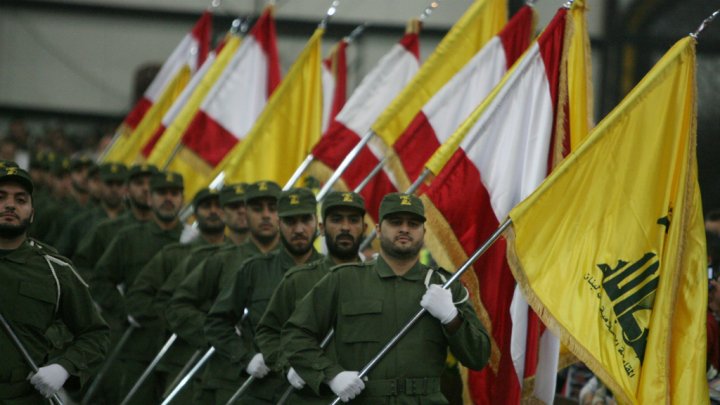

On Wednesday, March 2, the Saudi-led bloc of six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) nations designated Hezbollah a terrorist organization, taking the tensions a notch higher.

The move marked the latest twist in the fallout of the Syrian conflict, which has pitched Saudi Arabia against Iran, Hezbollah’s chief patron. With its 400-kilometer border with Syria and its diverse mix of religious groups — many of them armed and some rumoured to be arming themselves — Lebanon has been vulnerable to the shocks of the Syrian civil war over the past five years.

In a statement announcing the terror designation Wednesday, GCC Secretary-General Abdullatif al-Zayani said it was due to Hezbollah’s “hostile acts” within the bloc’s member states.

The Lebanese Shiite group is considered a terrorist organisation by the US and France, while the EU and Britain have proscribed its military wing. Although the Wahhabi Sunni Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is ideologically a natural foe of Iran-backed Hezbollah, the Saudis have long maintained a flexible, pragmatic policy toward Lebanon’s myriad factions, an approach that enabled Riyadh to broker the 1989 Taif Agreement that finally brought an end to the brutal Lebanese Civil War.

The recent deterioration of relations marks a break from the old Saudi way of doing business, according to Mohamad Bazzi, a professor at New York University currently writing a book on the proxy wars between Saudi Arabia and Iran. “This is significant within the context of Saudi policy,” explained Bazzi. “Saudi policy has been much more aggressive under the new King [Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, who was crowned in January 2015] than it has been for decades. The old status quo of using back channels and dialogue is gone. The new king appears to favour confrontation over accommodation.”

Economic salvo aimed at Lebanese people

The latest Saudi measure against Hezbollah appears to be more of an economic rather than a military salvo directed at the Lebanese people.

“Hezbollah doesn’t have any economic interests in the GCC. It’s not like the group has many bank accounts that can be frozen, which are the typical effects of such a terrorist organisation designation,” said Bazzi. “The biggest impact is likely to be felt by Lebanese and especially Lebanese Shia workers in the Gulf. We have already seen this being played out over the past few weeks, with the Saudis and the UAE expelling Lebanese nationals. It’s relatively easy to expel foreign workers by not renewing contracts or cracking down on residency statuses. It’s now much harder for Lebanese nationals who want to get work in the Gulf. It’s also much harder because diplomatic missions have been scaled back. So, the constant stream of migrants going back and forth has slowed down.”

According to Michael Young, opinion editor of the Beirut-based Daily Star, the terror designation can also be viewed as a symbolic warning. “It’s a political statement,” he explained. “Today, the Saudi position is to consider Hezbollah a threat and to signal that it’s willing to fight Hezbollah everywhere in the region.”

Keeping Hezbollah strong and the army weak

But the Saudi punishment has also extended to Lebanon’s fragile military, with potentially serious security implications.

Last month, Riyadh announced it was stopping payment on $4 billion (3.7 billion euros) worth of military aid to Lebanon because Beirut failed to condemn attacks on Saudi diplomatic missions in Iran following the kingdom’s execution of influential Shiite cleric Nimr al-Nimr.

The Saudi aid was destined to buy French weapons for the Lebanese army as part of a long-term plan to modernise the country’s weak military. Lebanon has already received the first batch of arms, which included armoured vehicles, attack helicopters, and artillery.

In an interview with Bloomberg, Sami Nader, head of the Beirut-based Levant Institute for Strategic Affairs, said the scrapping of military aid happened because Saudi Arabia was unable to ensure the French weapons would not fall into the hands of Hezbollah, whose fighters are supporting Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

As one of the main international backers of the largely Sunni opposition forces in Syria, Saudi Arabia has been alarmed by the tide of the Syrian conflict turning in favour of Assad and his Russian and Iranian-backers.

While Hezbollah is the most powerful military force in Lebanon, there have been concerted international efforts in recent years to strengthen the national army, considered one of the few unifying institutions in a deeply divided country located on the frontlines of the Middle East’s most destabilising conflicts.

Cutting the military aid would only entrench the Lebanese status quo with Hezbollah wielding more military might than the national army.

Reacting to the news of the Saudi scrapping of military aid, the Hezbollah-owned al-Manar website last month quoted an Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman promising that “the Islamic Republic of Iran is ready to provide Lebanon with the military support in case the latter asks for it.”

Analysts also warn that the Saudi economic punishment against Lebanon could backfire. “I’m not sure the Saudis have fully thought out the end game,” said Bazzi. “If the Saudi regime thought this would lead to an uprising or rebellion against Hezbollah in Lebanon, it’s actually more likely to have the opposite effect, particularly among Hezbollah supporters. The Shia community is going to be even more forced into Hezbollah’s arms. If people can’t go to work, they will become more reliant on Hezbollah for social services.”

‘A distillation’ of the region’s contradictions

On the domestic front, the Saudi-Iran proxy spat is not helping Lebanon’s longstanding political stalemate that has seen the country essentially leaderless since former Lebanese President Michel Suleiman’s term ended in May 2014. For the 36th time in a row parliament failed on Thursday to elect Suleiman’s successor.

Former Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri, a key ally of Saudi Arabia, has been walking a tightrope between the country’s opposing political power centres. In December 2015, Hariri made a bid for the prime minister’s post with Maronite Christian politician Suleiman Franjieh vying for the presidency. Hezbollah however opposed the Franjieh-Hariri ticket and the political stalemate dragged on.

Following the GCC decision to brand Hezbollah a terrorist organisation, Hariri blasted the Shiite group’s actions in the region. "What Hezbollah is doing in Syria and Yemen is for me criminal, illegitimate and terrorist," he said following Thursday’s failed bid to elect a president.

But he was careful to stress that his Future Movement political party would continue to hold talks with Hezbollah representatives. “Hezbollah has long been designated a terrorist group in the Gulf and that has changed nothing in Lebanon,” he said. “We will hold talks with those we have differences with…We will continue the dialogue because we do not want strife in Lebanon.”

The danger though is that the power games between Saudi Arabia and Iran being waged in Lebanon could well see civil strife break out in the tiny, fragile nation that is already coping with an influx of more than a million Syrian refugees and a political impasse.

But that, according to Young, has always been Lebanon’s fate. “Lebanon has always been a distillation of all the contradictions in the region. The latest Saudi measure is definitely not doing any good for Lebanon. But the same is true for Hezbollah’s actions in Syria. It’s not just one side responsible for this, they both are,” he said.

Date created : 2016-03-03