KFAR ZABAD, Lebanon (AFP) by Jocelyne Zablit – A decade ago, it was a glittering vision — a scheme to lure nature lovers to the Lebanese highlands, providing income to local people, nurturing the country’s damaged environment and cementing national unity in one stroke. Today, after a war, a political crisis and flareups of sectarian violence, Lebanon’s brave experiment in eco-tourism is battered and bloodied but defiantly soldiers on. In the eastern Bekaa region near the Syrian border, financial help from the United States and Europe helped establish a project for encouraging families to come and enjoy the wildlife, staying in local hostels and employing local guides. Ravaged by hunters, the countryside around the village of Kfar Zabad, which straddles the main migration route for African-Eurasian water fowl, was declared a protected area and now teems with birds, along with wildcats and a few river otters. "Before, this place was filled with hunters in the afternoon and all you heard was the sound of gunfire," Mayor Qassem Choker says proudly, pointing to fields near the entrance to the village. "But since the village was designated a protected area in 2004, we can hear the birds chirping again and enjoy our surroundings." The wildlife has emphatically returned. But since the 2005 assassination of ex-premier Rafiq Hariri that marked Lebanon’s new plunge into turmoil, the tourists have become an endangered species.

KFAR ZABAD, Lebanon (AFP) by Jocelyne Zablit – A decade ago, it was a glittering vision — a scheme to lure nature lovers to the Lebanese highlands, providing income to local people, nurturing the country’s damaged environment and cementing national unity in one stroke. Today, after a war, a political crisis and flareups of sectarian violence, Lebanon’s brave experiment in eco-tourism is battered and bloodied but defiantly soldiers on. In the eastern Bekaa region near the Syrian border, financial help from the United States and Europe helped establish a project for encouraging families to come and enjoy the wildlife, staying in local hostels and employing local guides. Ravaged by hunters, the countryside around the village of Kfar Zabad, which straddles the main migration route for African-Eurasian water fowl, was declared a protected area and now teems with birds, along with wildcats and a few river otters. "Before, this place was filled with hunters in the afternoon and all you heard was the sound of gunfire," Mayor Qassem Choker says proudly, pointing to fields near the entrance to the village. "But since the village was designated a protected area in 2004, we can hear the birds chirping again and enjoy our surroundings." The wildlife has emphatically returned. But since the 2005 assassination of ex-premier Rafiq Hariri that marked Lebanon’s new plunge into turmoil, the tourists have become an endangered species.

Foreign tourists and even expatriate Lebanese have been discouraged by fears about safety. The main visitors to the Bekaa are hardy people from Beirut and other regions, who in periods of relative calm grab the chance of a countryside break. "We keep trying to tell people it’s safe but the simple mention of the name Bekaa scares them away," said Dalia Al-Jawhary, of the Society for the Protection of Nature in Lebanon, which is heavily involved in the Kfar Zabad project. Faisal Abu-Izzedin, director of the Lebanon Mountain Trail project, a 440-kilometre (275-mile) path that cuts through 75 villages, many of them in remote areas stretching from the north to the south, says Lebanon offers unique treasures. "Nowhere else can you see this diversity," he said. "Our aim was to revive an ancient heritage which was a trail that connected villages. We hope that the trail and people who walk the trail will shine a light on the importance of keeping Lebanon beautiful." From the beaches along the Mediterranean, to mountains, forests, wildlife, Roman ruins and gorges — all within a few hours’ drive or walk — the country of 10,425 square kilometers (4,170 square miles) indeed has much to offer. "Lebanon has been classified among the 25 top countries in terms of biodiversity," said Pascal Abdallah, who heads Responsible Mobilities, an eco-conscious tour company. "We have 40 kinds of wild orchids, two or three of which are endemic to Lebanon. "We still have wolves in this tiny country, we have a type of hyena that only exists in the eastern part of the Mediterranean — and of course we have the cedars."

BEIRUT (AFP) – The Ottoman-style mansions, with Venetian windows, arches and lavish gardens that once epitomised

BEIRUT (AFP) – The Ottoman-style mansions, with Venetian windows, arches and lavish gardens that once epitomised  TRIPOLI, Lebanon (AFP) – Tension ran high in north Lebanon’s capital of

TRIPOLI, Lebanon (AFP) – Tension ran high in north Lebanon’s capital of  BEIRUT (AFP) – Two years after the worst oil spill in the east Mediterranean left thousands of tonnes of crude over three-quarters of Lebanon’s coast, the beaches are almost all clean but the troubles continue. In July 2006, in the midst of the month-long war between

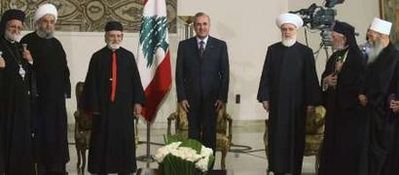

BEIRUT (AFP) – Two years after the worst oil spill in the east Mediterranean left thousands of tonnes of crude over three-quarters of Lebanon’s coast, the beaches are almost all clean but the troubles continue. In July 2006, in the midst of the month-long war between  President General Michel Suleiman spoke at a meeting of Lebanon’s top 15 Christian and Muslim religious leaders, who convened at the

President General Michel Suleiman spoke at a meeting of Lebanon’s top 15 Christian and Muslim religious leaders, who convened at the  Daily Star – BEIRUT: Miraculous, perhaps. Tens of thousands of Lebanese gathered in Martyrs Square in Downtown Beirut on Sunday to witness the beatification of Yaaqoub Haddad, the late Capuchin priest who gained fame for his prolific work in founding an order of nuns, expanding the Capuchin school network and conceiving or establishing a number of religious and social institutions, some of which have gained iconic status in Lebanon. Haddad, who died more than 50 years ago, took a step toward sainthood in the first beatification ever to take place outside the Vatican – and people flocked to the capital to observe the ceremony.

Daily Star – BEIRUT: Miraculous, perhaps. Tens of thousands of Lebanese gathered in Martyrs Square in Downtown Beirut on Sunday to witness the beatification of Yaaqoub Haddad, the late Capuchin priest who gained fame for his prolific work in founding an order of nuns, expanding the Capuchin school network and conceiving or establishing a number of religious and social institutions, some of which have gained iconic status in Lebanon. Haddad, who died more than 50 years ago, took a step toward sainthood in the first beatification ever to take place outside the Vatican – and people flocked to the capital to observe the ceremony.  highest honors in the Christian tradition upon a Lebanese priest mere meters away from an Ottoman-era mosque in the heart of the capital. Indeed, while respectful or appreciative clapping often arose, the loudest rounds of applause came after "the nation" or the "Lebanese cedars" were mentioned in one context or another. A procession of the cross was held before Western Catholic – Latinized – renditions of Syriac and Arabic Christian chants held the massive gathering rapt. As Cardinal Martins read out a message from the pope, "hoping that this beatification will lift Father Yaaqoub of Ghazir as a happy servant of the Lord," a white veil cloaking a portrait of the late priest was lifted, symbolizing recognition of Haddad’s beatification.

highest honors in the Christian tradition upon a Lebanese priest mere meters away from an Ottoman-era mosque in the heart of the capital. Indeed, while respectful or appreciative clapping often arose, the loudest rounds of applause came after "the nation" or the "Lebanese cedars" were mentioned in one context or another. A procession of the cross was held before Western Catholic – Latinized – renditions of Syriac and Arabic Christian chants held the massive gathering rapt. As Cardinal Martins read out a message from the pope, "hoping that this beatification will lift Father Yaaqoub of Ghazir as a happy servant of the Lord," a white veil cloaking a portrait of the late priest was lifted, symbolizing recognition of Haddad’s beatification.  "The righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their father," the Maronite patriarch said as he took the pulpit, evoking reverent silence through the assembled thousands. "The hope of so many Lebanese was realized today – that hope was the raising of Father Yaaqoub’s portrait above the altar of the Catholic Church." Sfeir then outlined how Haddad "passed through the narrow door leading to sainthood," attributing the priest’s ability to walk "the difficult road of a saintly life to three virtuous practices: surrender to the will of God, Christian modesty and the work of mercy." "Father Yaaqoub would say that ‘All God has given me belongs to Him and the poor of Lebanon," added Sfeir, in reference to his first point regarding the late pastor. "He built hospitals, schools and took care of the sick, yet he was a man of simple means – Father Yaaqoub put his trust in the grace of God." Sfeir, describing the four "pillars of modesty" that characterized Haddad’s life, again quoted the priest, saying: "Do not bestow virtue upon yourself that is not present within you; credit the Lord for that which is good in us; do not praise yourself in the presence of others; and do not count the shortcomings of those close to you in order to raise yourself."

"The righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their father," the Maronite patriarch said as he took the pulpit, evoking reverent silence through the assembled thousands. "The hope of so many Lebanese was realized today – that hope was the raising of Father Yaaqoub’s portrait above the altar of the Catholic Church." Sfeir then outlined how Haddad "passed through the narrow door leading to sainthood," attributing the priest’s ability to walk "the difficult road of a saintly life to three virtuous practices: surrender to the will of God, Christian modesty and the work of mercy." "Father Yaaqoub would say that ‘All God has given me belongs to Him and the poor of Lebanon," added Sfeir, in reference to his first point regarding the late pastor. "He built hospitals, schools and took care of the sick, yet he was a man of simple means – Father Yaaqoub put his trust in the grace of God." Sfeir, describing the four "pillars of modesty" that characterized Haddad’s life, again quoted the priest, saying: "Do not bestow virtue upon yourself that is not present within you; credit the Lord for that which is good in us; do not praise yourself in the presence of others; and do not count the shortcomings of those close to you in order to raise yourself."  by Omar Ibrahim, TRIPOLI, Lebanon (AFP) – Four people were killed and at least 33 others wounded in north Lebanon on Sunday in clashes between armed opponents and supporters of the parliamentary majority, security officials said. After a lull of several hours, the two sides traded fire with Kalashnikov

by Omar Ibrahim, TRIPOLI, Lebanon (AFP) – Four people were killed and at least 33 others wounded in north Lebanon on Sunday in clashes between armed opponents and supporters of the parliamentary majority, security officials said. After a lull of several hours, the two sides traded fire with Kalashnikov  By Michael Bluhm, BEIRUT: Israel’s Wednesday offer of direct peace talks with Lebanon amounts to little more than a ploy in domestic Israeli politics and a sop to US interests in the region without any hope for success, a number of analysts told The Daily Star. Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert has undertaken a flurry of diplomatic activity recently, with the disclosure last month of indirect Israeli-Syrian negotiations brokered by Turkey and the announcement on Tuesday of a six-month cease-fire with Hamas in Gaza, but his approval ratings have been at historic lows since Israel’s debacle in the summer 2006 war here. Olmert’s political epitaph may well have been written by the court testimony last month of an American businessman who said he loaded Olmert with cash-stuffed envelopes totaling more than $150,000 when the prime minister was mayor of Occupied Jerusalem. With Olmert’s political fortunes nearly bankrupt, Wednesday’s invitation for direct talks with Lebanon aims partly to deflect attention from his domestic difficulties, said political analyst Simon Haddad.

By Michael Bluhm, BEIRUT: Israel’s Wednesday offer of direct peace talks with Lebanon amounts to little more than a ploy in domestic Israeli politics and a sop to US interests in the region without any hope for success, a number of analysts told The Daily Star. Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert has undertaken a flurry of diplomatic activity recently, with the disclosure last month of indirect Israeli-Syrian negotiations brokered by Turkey and the announcement on Tuesday of a six-month cease-fire with Hamas in Gaza, but his approval ratings have been at historic lows since Israel’s debacle in the summer 2006 war here. Olmert’s political epitaph may well have been written by the court testimony last month of an American businessman who said he loaded Olmert with cash-stuffed envelopes totaling more than $150,000 when the prime minister was mayor of Occupied Jerusalem. With Olmert’s political fortunes nearly bankrupt, Wednesday’s invitation for direct talks with Lebanon aims partly to deflect attention from his domestic difficulties, said political analyst Simon Haddad.  by Hassan Jarrah

by Hassan Jarrah  By Mike Sergeant, They call it the "miracle of Lebanon" – the ability of this country to bounce back after a devastating war or political crisis. Only last month, violence erupted on the streets of Beirut. Lebanon seemed to be bracing for another civil war. But within weeks of a peace deal being signed in Doha, a president has finally been elected and tourists are returning to the Lebanese capital. Once again, the evenings are filled with the sound of young people having fun and music blaring from Beirut’s numerous bars and cafes. In some countries, it would take years for confidence and optimism to return after such a period of intense uncertainty. Not here. The Lebanese take huge pride in their ability to be crying one minute, and laughing the next.

By Mike Sergeant, They call it the "miracle of Lebanon" – the ability of this country to bounce back after a devastating war or political crisis. Only last month, violence erupted on the streets of Beirut. Lebanon seemed to be bracing for another civil war. But within weeks of a peace deal being signed in Doha, a president has finally been elected and tourists are returning to the Lebanese capital. Once again, the evenings are filled with the sound of young people having fun and music blaring from Beirut’s numerous bars and cafes. In some countries, it would take years for confidence and optimism to return after such a period of intense uncertainty. Not here. The Lebanese take huge pride in their ability to be crying one minute, and laughing the next.